Dual mobility: a review of the current state

Background: The dual mobility (DM) concept in total hip arthroplasty (THA), developed over 45 years ago, has evolved from a French innovation into a globally recognized solution for preventing prosthetic instability. A comprehensive understanding of its biomechanical principles, design variations, and the distinction between monobloc and modular systems is essential for optimal clinical application.

Objective of the Article: This article provides a detailed review of the dual mobility concept, tracing its historical development from the original Tripod cup to contemporary designs. It aims to elucidate the biomechanical principles underpinning its superior stability and range of motion, compare the performance of monobloc (DMC) versus modular (MDM) systems, and discuss the clinical relevance of different prosthetic designs.

Key Points / Core Message: The core principle of DM involves two articulations, providing an unmatched combination of increased range of motion and enhanced stability. This is characterized by a significantly greater "jump distance" compared to conventional implants, resulting in exceptionally low dislocation rates (0.4% at 10 years in a large series). The evolution to symmetrical, cylindro-spherical designs has further optimized intrinsic stability. The article highlights the biomechanical superiority of the original monobloc DMC concept over MDM systems, which are associated with reduced stability due to smaller liner diameters and risks of fretting corrosion and metal ion release at the modular junction.

Conclusion / Implications for Practice: The dual mobility concept is a proven and durable solution in THA that effectively addresses prosthetic dislocation, with excellent long-term survival. A critical takeaway for surgeons is the biomechanical advantage of monobloc, cylindro-spherical DMC designs over modular MDM systems, which carry inherent risks of instability and adverse local tissue reactions. DM stands as a benchmark in modern hip replacement surgery.

Introduction

Dual Mobility is an old concept (patent dating from 1976) conceived by Gilles Bousquet (1936-1996), a member of the Lyon School of Orthopaedics and a Professor at the University Hospital (CHU) of Saint-Etienne. Thanks to the ingenuity of André Rambert, founder of the SERF company, the Tripod Cup was brought to fruition in 1979 (Figure 1), meaning this concept has been in existence for over 45 years. Initially, it was a hemispherical stainless steel cup with lateral fins, into which two ischial and pubic anchoring pegs and an iliac anchoring screw were inserted to ensure its primary stability. Secondary fixation was anticipated from an alumina spray coating. For 20 years, this was the only system available, distributed by SERF. SERF is the historical distributor and remains the world leader today.

In collaboration with Rémi Philippot and Frédéric Farizon, we had the opportunity to review a historical series of Gilles Bousquet's patients at a 10-year follow-up. This series comprised 106 consecutive patients, residing in Saint-Etienne, who received implants between 1993 and 1994. All had been fitted with a Tripod cup, articulating with a Serf PRO screwed femoral stem (Figure 2). The overall Kaplan-Meier survival at 10 years was 94.6%; this survival rate increased to 98% in subjects over 50 years of age.

There were no dislocations in this series, which all utilised a posterior approach.

There was, however, a specific complication associated with dual mobility: intra-prosthetic dislocation, defined as the dissociation of the retentive polyethylene from the prosthetic head. This occurred at a rate of 2%, but this complication has since been eliminated.

In the late 1990s, the patent entered the public domain, and from this period onwards, a profusion of cups were introduced to the market. This competition spurred the development of progressive improvements to the system:

- press-fit fixation

- a chamfer on the edge of the polyethylene

- new designs

- optimisation of surface treatments

- improvements in polyethylenes

Today, the dual mobility system is the best-selling system in France; its use has become worldwide. International publications on the subject have grown exponentially since the 2009 SoFCOT (French Society of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery) symposium.

If, for Ian Learmonth, total hip arthroplasty is the operation of the century, following its original conception in the early 1960s by Sir John Charnley, how many prosthesis models have since been forgotten and abandoned? Dual Mobility has stood the test of time. Today, having passed through generations, it is a concept that has successfully convinced the surgical community.

"The object of total hip replacement is to build well for 20 years; it is not for sensational short-term results" - Sir John Charnley

Definitions and principles

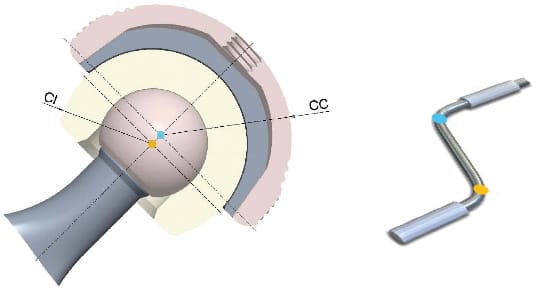

Dual Mobility is an original and revolutionary concept in the world of hip arthroplasty. The prosthetic head is mobile within a retentive polyethylene liner, which itself remains free to move within a metallic cup fixed into the acetabulum. This polyethylene moves via two articulations: one large-diameter articulation with the cup, and another small-diameter articulation with the prosthetic head (Figure 3).

This smooth metallic surface can be:

- monobloc, directly impacted into the host bone

- or placed into a metal-back shell.

When the system is monobloc, it is referred to as a dual mobility cup (DMC), which corresponds to the original French concept of dual mobility.

When the metallic surface is implanted into a metal-back shell, it is known as a modular dual mobility (MDM) liner, placed within a metal-back shell that is fixed to the host bone. This is a modular MDM system.

This is entirely different from the Tripolar Cup, an intermediate prosthesis that moves within a polyethylene liner fixed into a metal-back shell.

Dual mobility is therefore a truly original concept. In dual mobility, the polyethylene moves on the head and moves within the cup; there are indeed two mobilities. This system is in contrast to conventional systems where the polyethylene is fixed within the metal-back shell; there is only one mobility.

In principle, it is the small articulation that moves during normal function for purely mechanical reasons, according to the physical laws of moments. However, when the movement becomes extreme, the second articulation is engaged by contact between the prosthetic neck and the retentive rim of the polyethylene liner. This contact between the neck and the polyethylene constitutes the third articulation, a term established since the work of Daniel Noyer.

The advantages of such a concept are well known

In total hip arthroplasty, the dual mobility concept allows for a range of motion that no other system can achieve. Furthermore, this concept provides very high joint stability, again, unlike any other system. Dual mobility thus presents the paradox of optimised stability despite increased mobility.

Increased range of motion

The first mobility (Figure 4), i.e., the mobility between the head and the concavity of the polyethylene liner, provides a cone of motion that depends directly on the characteristics of the dual mobility liner (dimensional characteristics of the retentive rim and the chamfer design). This cone of motion also depends directly on the characteristics of the femoral implant, such as neck diameter and head diameter. With the NOVAE® implant (Serf, Stryker), using an 11 mm neck and a 22.2 mm head, the first mobility allows for a constant cone of motion of 51°. The use of a 28 mm head allows for a constant cone of motion of 76°. Increasing the neck diameter decreases this cone of motion.

Regarding the second mobility (Figure 4), which is the movement between the convexity of the polyethylene liner and the metal-back shell, the cone of motion increases with the cup diameter. For a 43 mm implant, the cone of motion is 126°; it increases to 140° for a 65 mm implant. The femoral neck diameter plays a minor role; this cone remains independent of the head diameter.

For a 53 mm cup inclined at 45° with 20° of anteversion, articulating with a stem featuring an 11 mm diameter neck, 15° of antetorsion, and 7° of valgus, the abduction/adduction range is 126°, flexion/extension range is 186°, and rotation reaches 220°.

If we extrapolate the results published at the AAOS in 2000 by Harkess (Figure 5), who studied the cone of motion for different types of polyethylene liners, it appears that dual mobility provides the greatest range of joint motion. It is greater than that of a standard implant and significantly greater than that of a liner with a posterior anti-dislocation wall. Indeed, along with the large-diameter metal-on-metal bearing, it is the only method whose mobility curve encompasses the circumduction curve of a normal subject, and even that of a trained individual, with ranges of motion exceeding usual norms.

Optimal prosthetic stability

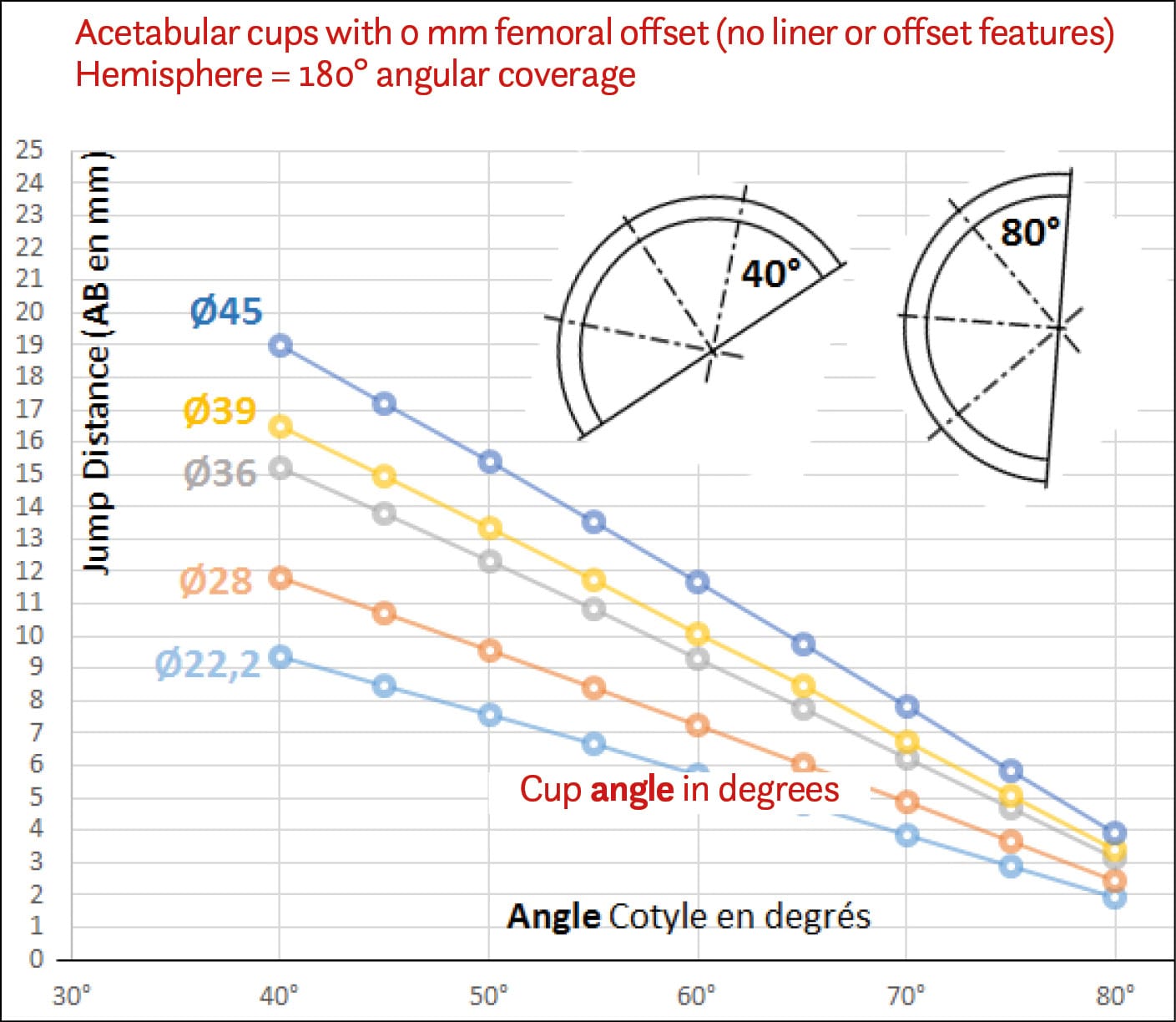

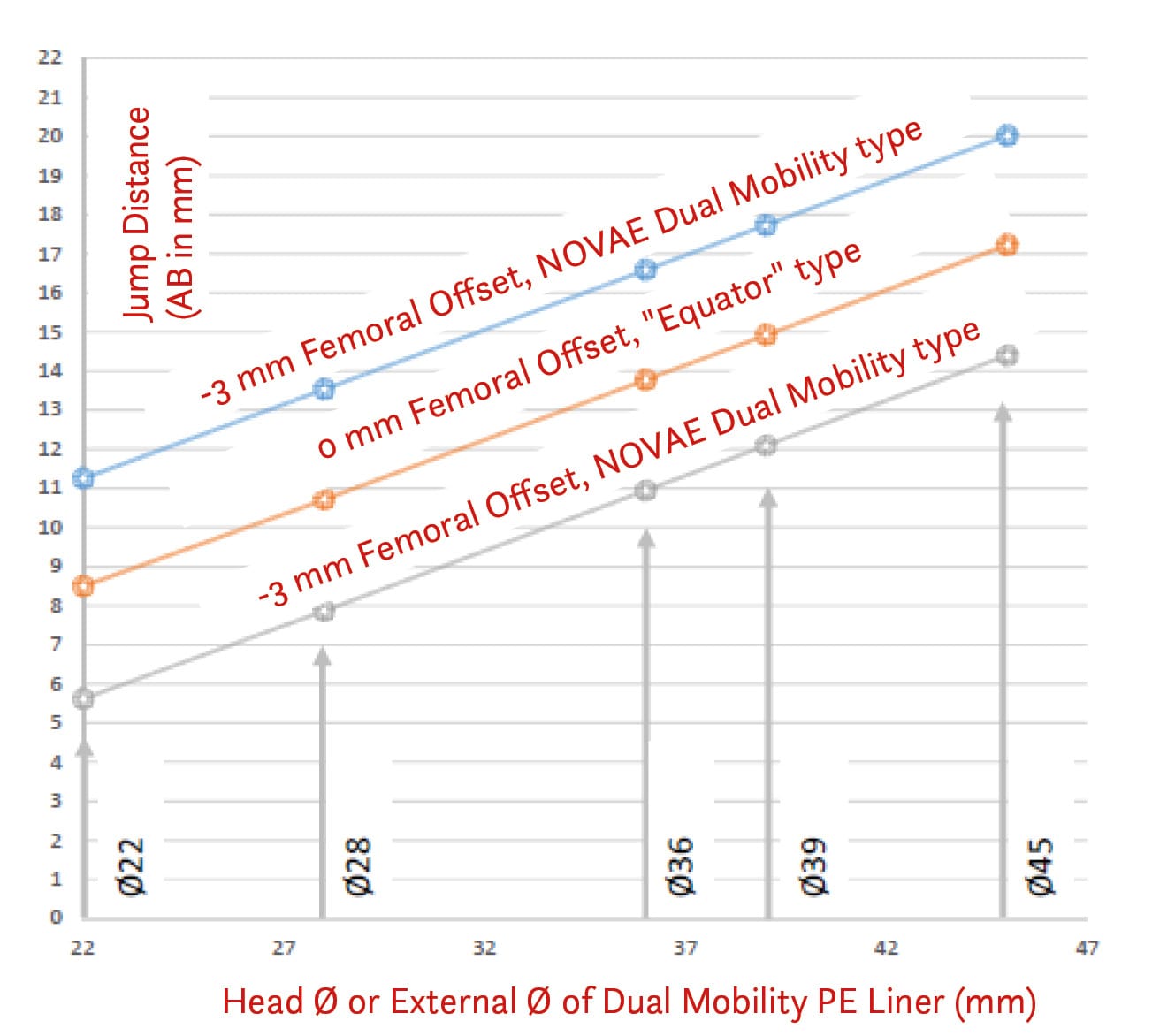

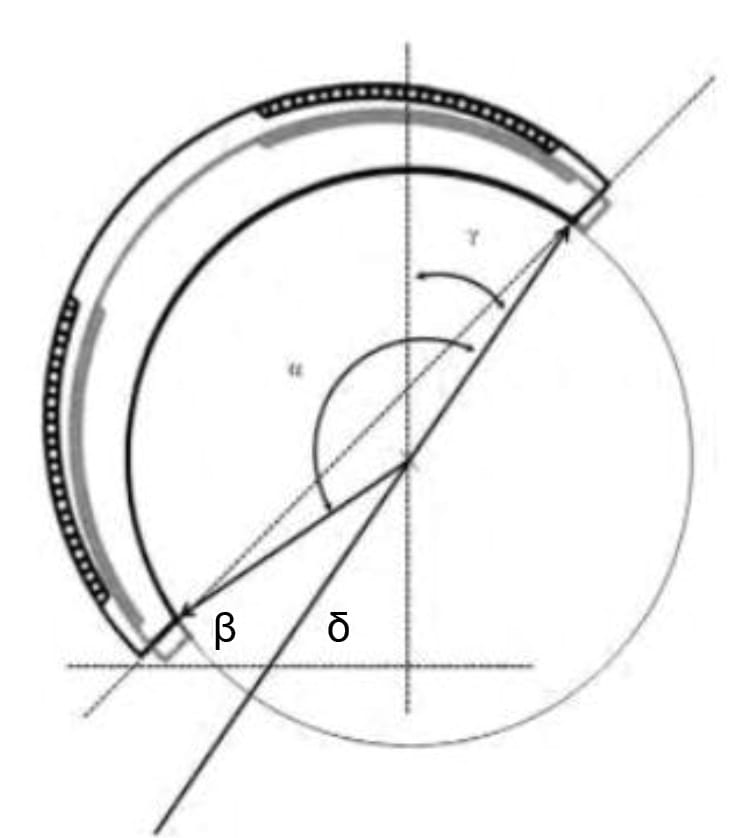

Joint instability occurs through two mechanisms: it can be due to decoaptation (separation of joint surfaces) or a cam effect (impingement). In either case, cam effect or decoaptation, the state of separation remains the same; dislocation occurs when the head moves from point A to point B. The risk of dislocation can be considered to decrease as the distance AB increases. AB is a function of the head radius R, the depth of the cup, and also the degree of inclination. AB, or the "jump distance", characterises a system or configuration in terms of dislocation risk.

Through geometric construction, it is possible to define the distance AB (Figure 6):

\[ \overline{AB} = R \times \sqrt{2 \times (1 - \cos\alpha)} \]

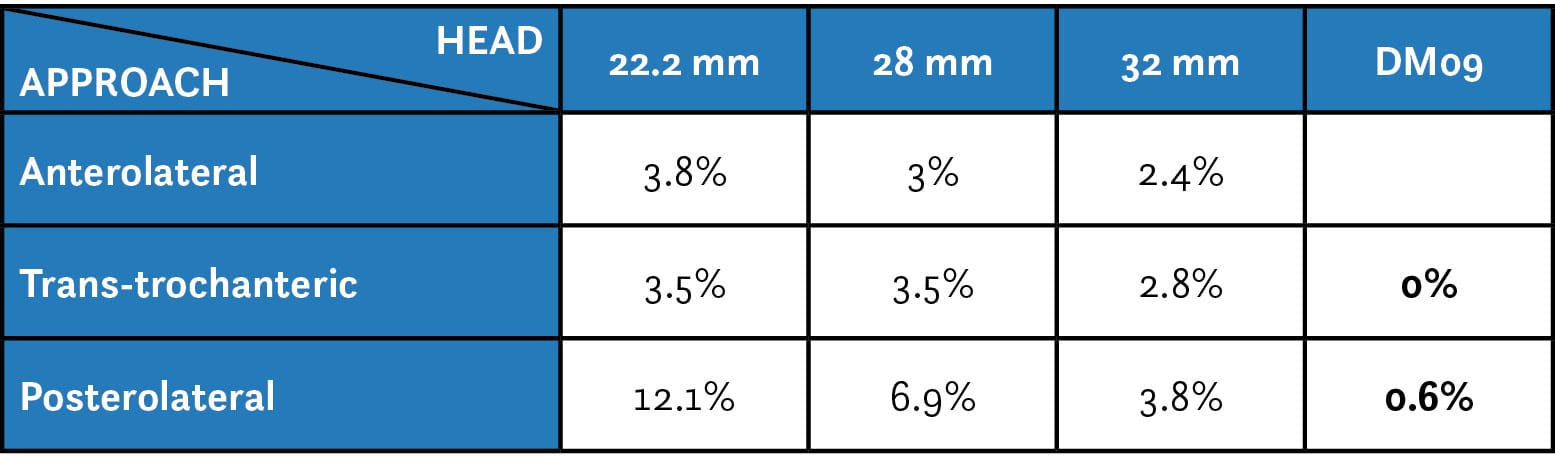

Thus, it appears that for the same configuration, the dislocation risk is greater for a 22 mm head than for a 28 mm head. D. Berry, in an earlier study, confirmed these theoretical results in a clinical setting; he emphasised the role of head diameter and also stressed the determining influence of the surgical approach. In 2005, D. Berry analysed 868 dislocations out of 21,047 total hip arthroplasties. The cumulative risk of dislocation, regardless of the surgical approach, was 2% at 1 year, 3% at 5 years, 4% at 10 years, and 6% at 20 years. The incidence of dislocation decreases as the head diameter increases. The posterolateral approach is most prone to dislocation.

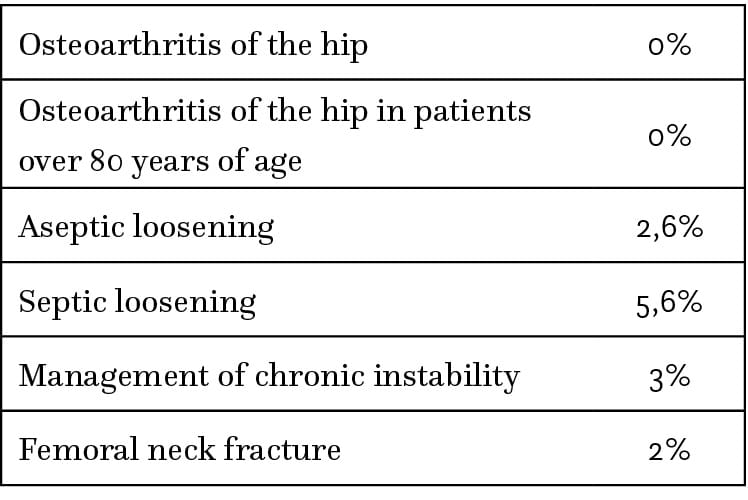

With this same posterior approach, the cumulative risk at 10 years for a 22.2 mm head is 12%; it drops to 7% for a 28 mm head and falls to 4% for a 32 mm head (Table I).

It is possible to apply the formula for determining the distance AB to dual mobility, and to define the distance AB that the polyethylene liner must travel to reach the point of dislocation. In dual mobility, this distance AB increases with the diameter of the cup.

If we accept that this distance AB characterises the system in terms of prosthetic stability, dual mobility currently appears to be the best solution to combat this risk. This is because, with dual mobility, the distance AB is the greatest. For an equivalent cup diameter, for example, the distance AB is greater with dual mobility than with a large-diameter metal-on-metal bearing or any other conventional system (Figure 7).

It should be noted that the jumping distance varies with inclination: the more vertical the cup, the less important the role of the head diameter becomes. Like any cup, dual mobility must adhere to strict criteria for correct positioning.

At the 2009 SoFCOT symposium, with a dual mobility system, across 3,473 primary surgery cases, the dislocation risk at 10 years was 0.4%, all surgical approaches combined. This risk was 0.6% for the posterior approach (Table 1).

Our department's case series show unparalleled efficacy in terms of prosthetic stability, with low cumulative dislocation rates.

The international literature today confirms this unmatched stability.

The literature demonstrates that using a head diameter greater than 32 mm eliminates the influence of the surgical approach on stability.

Unlike a conventional system, in the event of a dislocation in primary surgery, there is no recurrence with dual mobility. A conventional system has a recurrence rate of at least one in two.

A possible reduction in loosening stresses at the interface

It has often been suggested that dual mobility may reduce the transmission of stresses to the interface with the host bone. We attempted to set up a test bench to characterise these stresses and to compare them between a standard system and a dual mobility system. We were able to demonstrate a difference, but is it truly significant?

Prosthetic design

The original design of the tripod cup

Originally, the Tripod implant was a so-called "peaked" cup (cupule à casquette). The designer started with a hemisphere, to which he added a superior iliac peak and created a cut-out in the hemisphere at the level of the obturator foramen (Figure 8). This design was criticised, probably unjustly, for causing impingement with the iliopsoas muscle.

When the patent entered the public domain, manufacturers retained this principle of a superior peak.

From the tripod cup to the NOVAE SUNFIT® cup (Serf, Stryker)

The modern SERF STRYKER cup is a cylindro-spherical cup, an evolution of the original design. While maintaining the same coverage of the polyethylene, i.e., preserving the same jump distance, the peaked and finned aspects have been eliminated. The resulting perfectly symmetrical cup can be positioned as desired by the surgeon to avoid any conflict with superior or anterior soft tissues, on the one hand, and any prosthetic neck-cup impingement on the other.

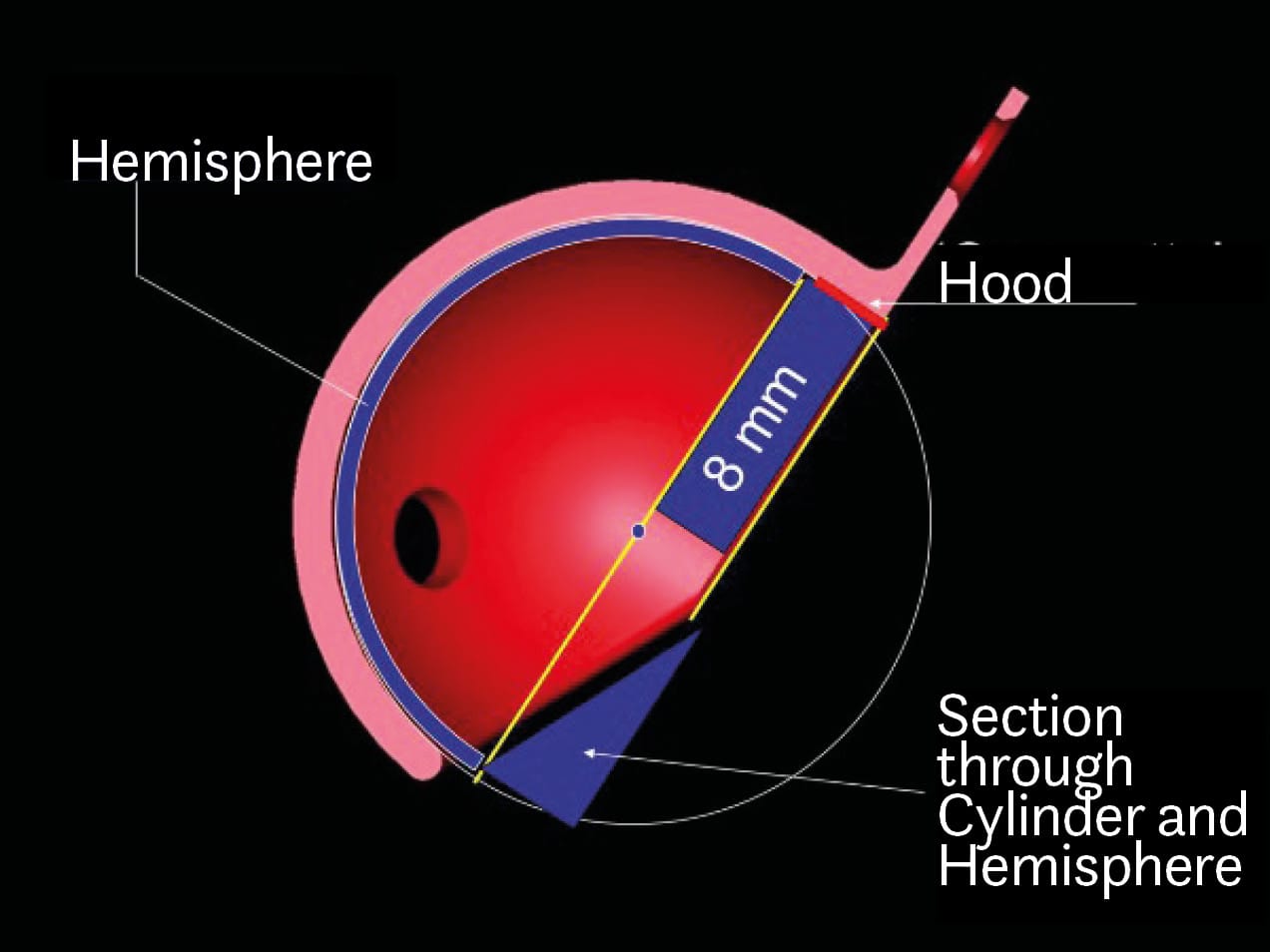

The cup is designed as follows (Figure 9):

- from the obturator point O, the diameter of the sphere is drawn;

- a hemisphere is created, adding an angular coverage of 12°;

- it is important to emphasise this concept of coverage with perfect congruence between the metal-back and the polyethylene, which was not the case in the initial model;

- then, a 3 mm cylinder is added to this hemisphere to maintain the same jump distance as the Tripod cup.

While the original peak measured 8 mm relative to the hemisphere, the cylindro-spherical design achieves the equivalent of such a peak with only 3 mm of extra material, whilst maintaining the same jump distance.

Among the dual mobility systems on the market, this is the system that offers the largest jump distance, thereby conferring unparalleled intrinsic mechanical stability to this implant. This is one of the reasons why this design is being increasingly copied.

Several teams insist that this cylindro-spherical shape facilitates an effective and secure grip for the insertion instrument on the cup for positioning, which is all the more important as surgical approaches are often smaller. This is a second reason driving the market towards this design.

The peak and the augmenting cylinder are often utilised - though this is not mandatory - to increase the contact surface between the cup's surface treatment and the healthy host bone, which facilitates secondary fixation of cementless cups.

The different designs on the market

Observing the implants available on the market, there seems to be great variability and diversity of shape; however, this is not the case. The design can exceptionally be asymmetrical. This is the case for an anatomical cup, the Stryker ADM cup. In this instance, there is a specific cup for the right side and another for the left. Psoas impingement was the primary cause of late complications in the series presented at the 2009 SoFCOT dual mobility symposium. In this series, its incidence was 2.1%, ahead of infection and intra-prosthetic dislocation. The benefit of an asymmetrical anatomical cup with an anterior cut-out is to avoid any anterior prosthetic overhang responsible for conflict with the iliopsoas muscle. The cup's design is based on the anatomical work of Maruyama and the anatomical and radiological studies in 2007 and 2008 by Vandenbussche, the promoter of this anatomical cup. His work identified a postero-superior defect on the anatomy of the acetabular rim. This has an average depth of 5 mm, with three different shapes: straight (15%), curved (57%), and irregular (28%). As for the so-called "psoas valley", it has an average depth of 5 mm, also with three shapes.

Most cups have a symmetrical design: the Novae® range (Serf, Stryker), the Quatro cup (Lepine), the Avantage cup (Biomet Zimmer), the Polar Cup (Smith & Nephew)... Three main designs can be distinguished (Figure 10):

- spherical

- peaked (à casquette)

- cylindro-spherical

The convergence towards a symmetrical, cylindro-spherical shape

Symmetrical implants are used interchangeably on the right or left hip. The asymmetrical, anatomical design requires a specific cup for the right side and another for the left. This necessitates larger hospital inventories. This induces a cost for the manufacturer due to tied-up capital.

Prosthetic design conditions intrinsic stability performance

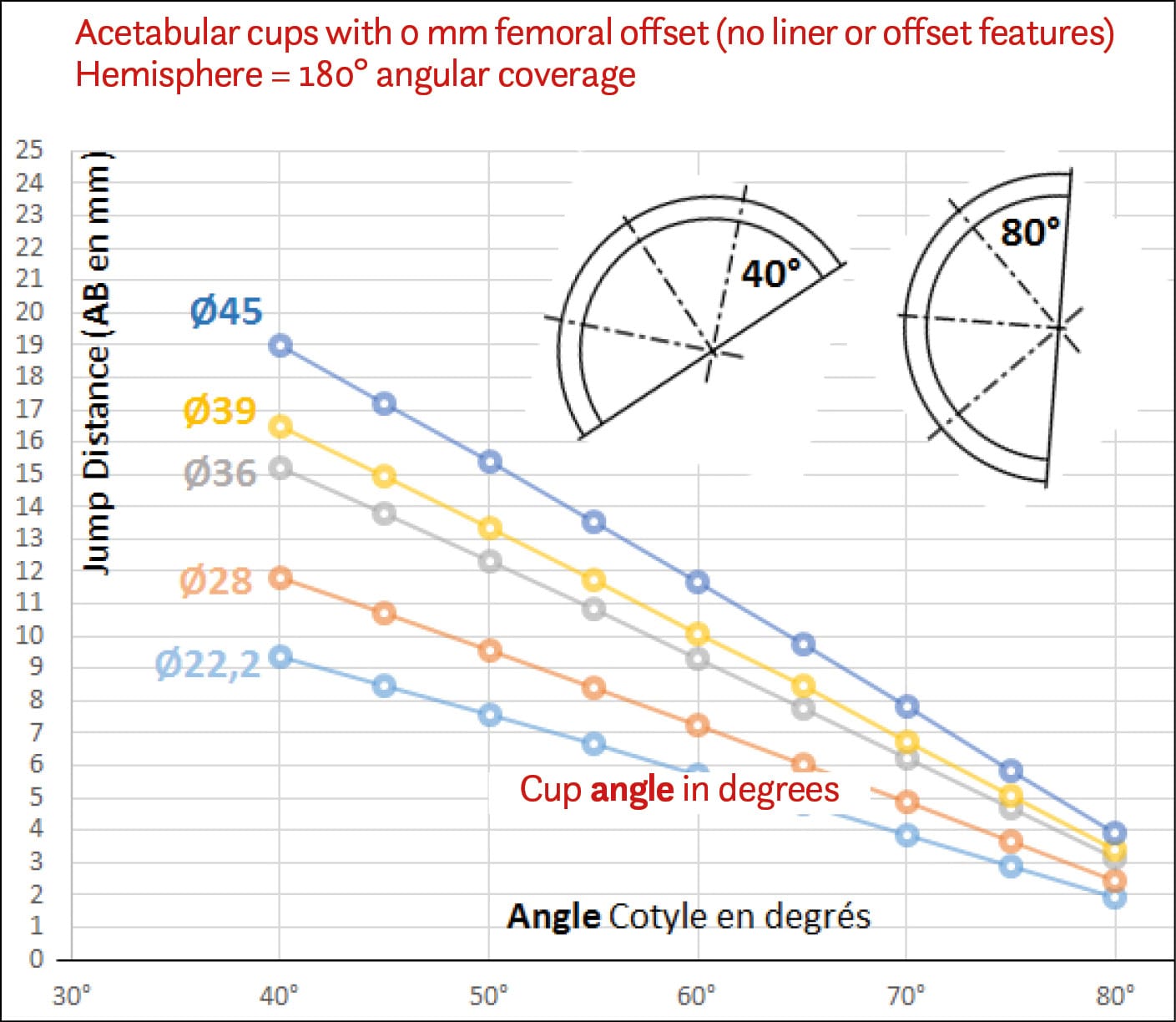

The jumping distance, which characterises mechanical stability, depends on:

- the cup inclination, a surgical factor (Figure 7)

- the prosthetic head diameter, a femoral factor,

- the cup coverage, an acetabular factor

The cup's opening angle or articular coverage angle is usually 180°; this is the angle (angle α) between the head's centre and the cup's rims. The position of the head's centre relative to the cup's equatorial plane is called the head offset.

The head offset is positive if the head's centre is located beyond the cup's equatorial plane. An example of this is a Metal-on-Metal (MoM) cup (Figure 11).

The head offset is negative if the head's centre is located inside the cup's equatorial plane. This is the case in a cylindro-spherical dual mobility cup (Figure 12).

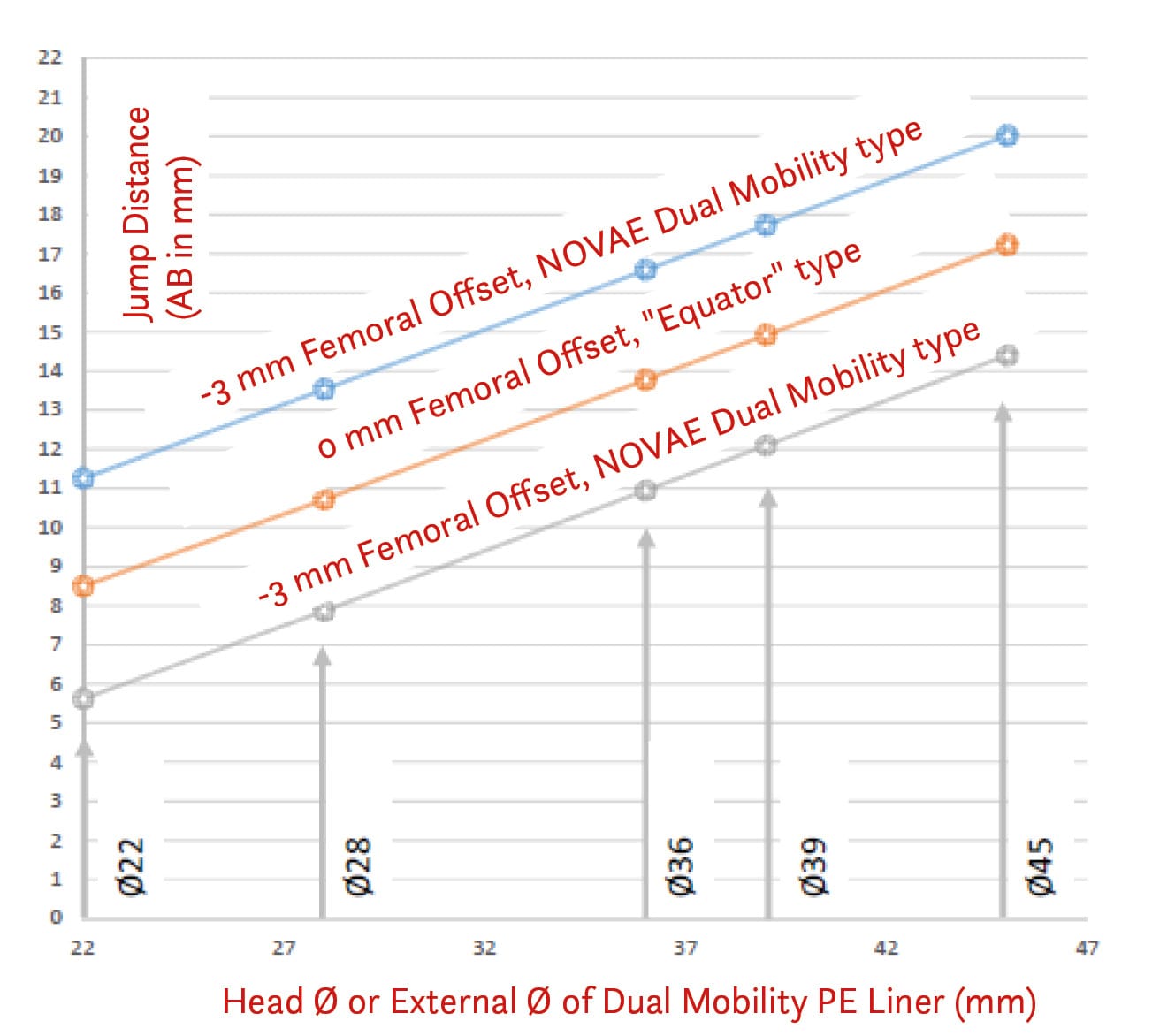

The dual mobility cup provides more or less coverage depending on whether its design is hemispherical (head offset is 0 mm) or cylindro-spherical, i.e., a hemisphere extended by a 3 mm cylinder (head offset is -3 mm).

The head offset is +3 mm in a MoM cup. This creates a differential in terms of jumping distance of at least 20% in favour of the cylindro-spherical dual mobility cup compared to the hemispherical design (Figure 13).

The peaked dual mobility cup presents a progressive gradient of stability, depending on the chosen direction, between the hemispherical and the cylindro-spherical shapes.

If the head offset is negative, the coverage is increased by an angle τ, and AB increases according to the formula in (Figure 14).

Stability of a DMC versus a MoM cup

This subject must be addressed because some authors have mistakenly proposed converting in-situ MoM cups to accept a dual mobility polyethylene liner. The literature reports an experience with the Magnum cup (Biomet). The jumping distance of the Magnum cup is very small due to the cup's prosthetic design. It is a hemispherical metal-back shell with a 180° external profile. The thickness of the metal-back shell is 6 mm at the pole and 3 mm at the equator. The head's centre of rotation is located eccentrically, outside the equatorial plane. This is what is termed the head offset. In the Magnum cup, it is +3 mm. The cup's opening angle (or articular coverage angle, usually 180° or more in dual mobility), i.e., the angle between the head's centre and the cup's rims (angle α), varies from 157° to 165°. The internal diameter of the cup, which is the diameter of the polyethylene, is the cup diameter minus 12 mm. This is because the Magnum cup has a significant thickness, as it was initially designed for a metal-on-metal bearing head. This substantial thickness ensured resistance to deformation during impaction so as not to alter the articular clearance. This specific design of the Magnum cup is completely opposite to the usual design of a dual mobility cup.

If we take the example of the NOVAE® cup (Serf), the difference between the polyethylene diameter and the cup diameter is 6 mm, because the cup thickness is only 3 mm. The dual mobility cup is more covering because it is a hemisphere extended by a 3 mm cylinder, giving it a head offset of -3 mm. We have already noted that the head offset is +3 mm in the Magnum cup. This creates a very significant differential in terms of jumping distance between a dual mobility cup and the Magnum cup (Figure 13). The jumping distance increases with head diameter. For an average 51 mm diameter Magnum cup, the liner measures 51 - 12 = 39 mm, whereas in a dual mobility system, the polyethylene (PE) liner for a 51 mm cup measures 51 - 6 = 45 mm. There is therefore a 6 mm differential between the liner diameter of a Magnum cup versus a classic dual mobility cup. The combination of these two detrimental effects (positive head offset and reduced diameter polyethylene) leads to a major degradation of the jumping distance in the Magnum cup compared to a dual mobility cup in the classic sense of the term (Figure 13).

For all these reasons, one should not convert a well-fixed metal-back shell from a large-diameter metal-on-metal bearing to a dual mobility system during a revision surgery. First and foremost, this is an assembly not intended by the manufacturer holding the CE mark.

The role of effective cup inclination in stability should not be forgotten

In the literature, incorrect positioning of the cup is a factor for instability. Analysis of the inclination on an anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis (Figure 15) gives a radiographic inclination β. This radiographic inclination β is different from the effective inclination δ, which is measured according to the formula:

δ = β - (180 - α/2)

If the cup is hemispherical or peaked, the radiographic inclination is the effective inclination.

If the cup is cylindro-spherical, the radiographic inclination underestimates the effective inclination. In the NOVAE® cup (Stryker Serf), the cup is a hemisphere extended by a 3 mm cylinder regardless of the diameter; the effective inclination is the radiographic inclination increased by 5° to 7° from the largest to the smallest cup. This covering nature of the cup smoothes out imperfections in positioning, without compromising stability or increasing wear phenomena on the convexity.

In other words, for the same positioning at 47° of radiographic inclination, a hemispherical or peaked cup has an effective inclination of 47°; a cylindro-spherical cup has an effective inclination of 40°, resulting in an increased AB distance. A cylindro-spherical cup with an excessive radiographic angle of 55° inclination still remains within the effective norms of positioning.

In the metal-back of a large-diameter MoM couple, the effective inclination is underestimated by approximately 8° compared to the measured radiographic inclination (δ = β - 8°).

All this explains the abnormally high rate of dislocation reported in the literature for MoM cups converted to dual mobility, a non-compliant configuration.

MDM versus DMC

Dual mobility consists of a polyethylene liner mobile on a prosthetic head, which articulates within a smooth metallic surface. When this metallic surface is implanted into a metal-back shell, it is a dual mobility liner placed within a metal-back shell fixed to the host bone. This is a Modular Dual Mobility (MDM) system (Figure 16).

It was Stryker that introduced the Dual Mobility concept to the United States after FDA validation in 2009 for the Stryker Anatomical Dual Mobility and the modular system in 2011 with the Stryker Modular DM. Many manufacturers today offer an MDM system; the best known remains that of Stryker, a pioneer in this venture.

Real but limited advantages of MDM

• Fixation by screws

The first advantage of the MDM system is the possibility, as in any conventional system, to place fixation screws through the metal-back shell towards the sacroiliac joint, as offered by any cementless system.

• Polar hole

The second advantage is the presence of a polar hole on the metal-back shell, which allows confirmation of the cup's correct seating against the host bone after impaction.

• A versatile choice in a universal system

The third advantage of modularity is that it leaves the surgeon the choice, once the metal-back shell is fixed and stabilised, between a standard single mobility liner and a Dual Mobility liner.

Within the single mobility option, they can choose their bearing couple: highly cross-linked polyethylene or ceramic, metal-on-metal. In case of insufficient stability intra-operatively, they can then change their option to a dual mobility liner. It is the same universal metal-back shell that can accommodate all these possibilities. It is therefore a versatile system that offers all possible alternatives and changes in strategy intra-operatively, based on trial reductions. It is a 4-in-1 cup, due to the 4 liner possibilities offered.

This versatile and universal system also allows for a reduction in hospital inventories, which is of financial interest to the manufacturer. This versatility could also reduce the risk of errors during the distribution of implants in the operating theatre.

The numerous disadvantages of MDM

Modular dual mobility (MDM) poses problems related to:

- the metallic thickness of the system, which is greater than in a DMC system

- the connection of the modular components

The Serf-Stryker DMC system has a cup thickness of 3 mm at the radius. With the Stryker MDM system, Trident Hemispherical Shell, the combined thickness of the cup and the liner is approximately 5 mm at the radius. In MDM, there is an increase in the radius of 2 mm, at the expense of the liner's diameter. This has several consequences:

• Restriction of the prosthetic range

The Serf DMC system covers a range from 41 mm to 69 mm. The Stryker MDM system offers a range that only begins at 46 mm.

• Restrictions on head diameter

With the French DMC system, a 28 mm head can be used while respecting the polyethylene thickness standards from a diameter of 47 mm upwards (PE thickness of 6.1 mm), whereas this is only possible for a Stryker MDM Trident Hemispherical Shell from size 52 mm upwards. The choice of head diameter is important in terms of polyethylene wear but also to avoid impingement of the neck against the retentive rim of the dual mobility liner, which ensures retention of the prosthetic head in its socket. The reduction in the head-to-neck ratio could lead to the reappearance of intra-prosthetic dislocation in case series.

• Detrimental effect on jumping distance

The metallic thickness imposed by the MDM system leads to a decrease in the PE diameter. The diameter of the polyethylene is the factor that defines the system in terms of stability. The jumping distance is considerably reduced, as illustrated in Figure 17.

The modular connection is a source of metal ion release. The recent history of orthopaedics has demonstrated the harmful nature of metallic ions in the joint, causing effusions, osteolysis, and tissue reactions. The literature warns about the release of these metallic ions in MDM systems. The junction of the cobalt-chrome liner on the titanium shell, via a Morse taper, generates the release of metallic ions through a mechanism of fretting corrosion, combined with galvanic corrosion.

Prosthetic eccentricity increases fretting corrosion. The introduction of a metallic liner into a metal-back shell leads to an eccentricity of the hip's centre of rotation, as the centre of the Dual Mobility liner does not superimpose on the centre of the metal-back shell (Figure 18). There is indeed a non-superimposition of the liner's centre and the metal-back shell's centre. There is a positive offset. This eccentricity of the centre of rotation gives rise to a crankshaft effect. This crankshaft effect generates a torque that contributes to increased degradation and the release of metallic ions at the Morse taper by increasing fretting corrosion (Figure 18). This risk of ion release is increased in the event of liner malpositioning. It is known from the literature that there is a significant rate of defective placement of this Dual Mobility liner (poor implantation or malseating: Romero 5.8%, Guntin 6.8%); its malpositioning generates a catastrophic degradation of the interface with a massive release of metallic ions.

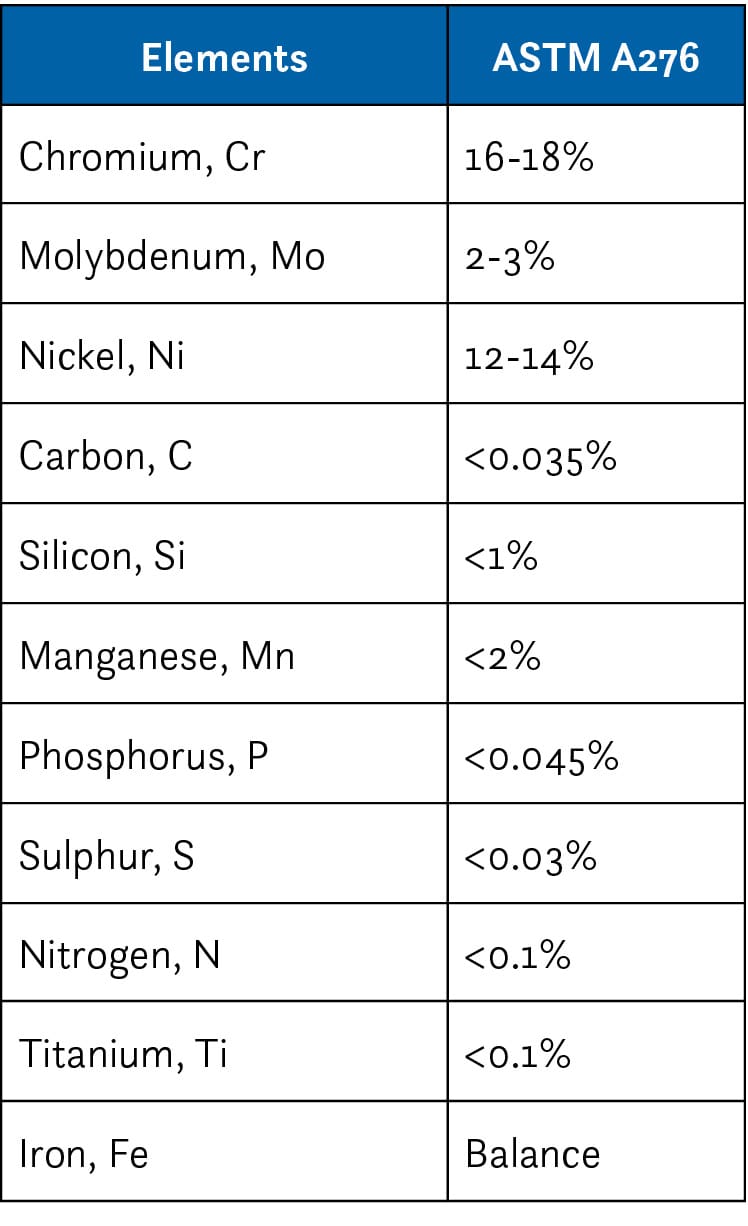

The nature of the materials

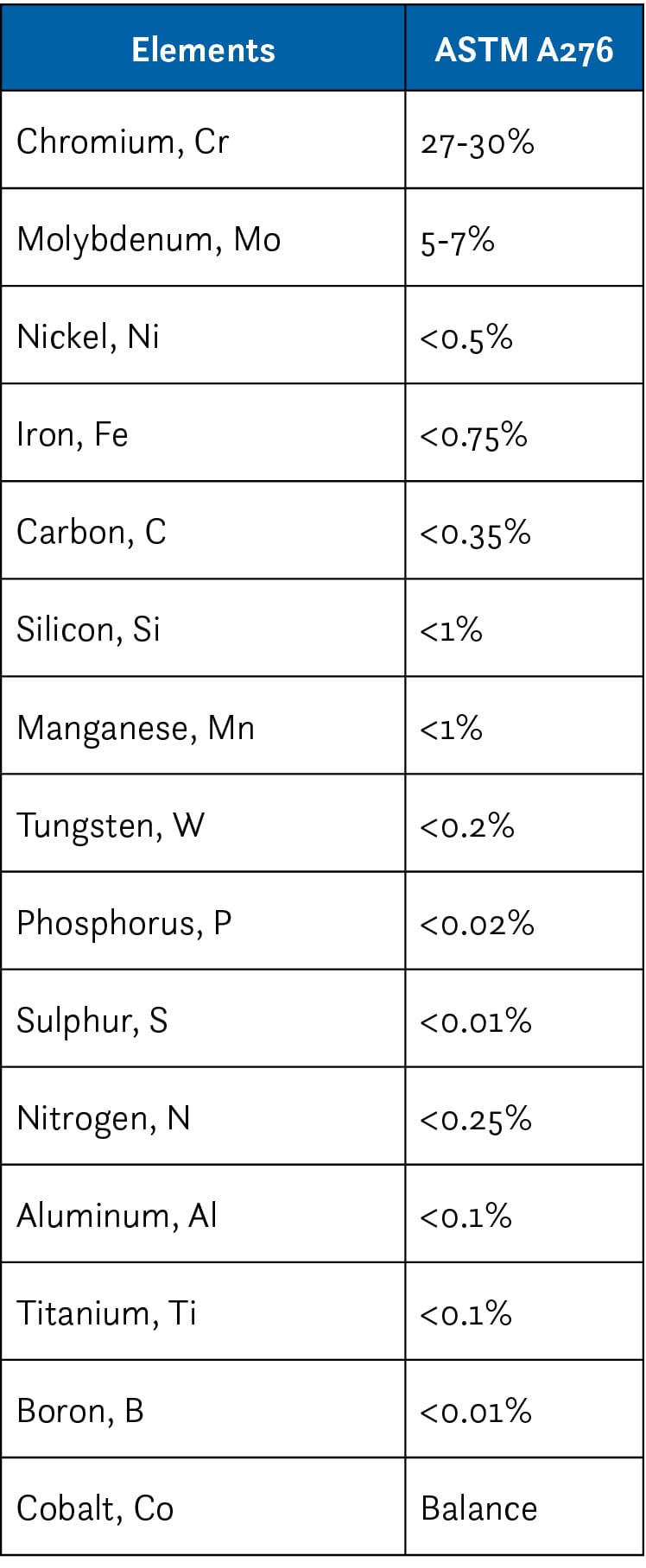

316L Stainless Steel or Cobalt-Chromium-Molybdenum

A frequently misunderstood issue for the surgeon: on the market, there are cups made of cobalt-chrome and cups made of 316L stainless steel. The experience with titanium in the 1990s was quickly halted. While titanium certainly has excellent osteoinductive properties for secondary fixation, it remains a very poor bearing surface. The composition of the alloys is different. The composition of cobalt-chromium-molybdenum is different from that of stainless steel (Tables 2 & 3). Both alloys contain chromium, which allows for passivation of the metal, conferring high-performance mechanical and electrochemical characteristics. The chromium is oxidised on the surface; when mixed into a solid component, chromium has no reaction with any body external to the alloy. This stainless alloy can therefore be used in the human body without any biocompatibility problems; this has indeed been the case since the beginning of the last century. Note the low carbon content in both alloys to avoid a deleterious effect on physical and mechanical properties. Also, note the very low titanium content so as not to degrade the tribological properties.

Mechanical properties

Cobalt-chrome has high hardness, more so than stainless steel; stainless steel, for its part, is more ductile. The ductility of a material refers to its ability to deform plastically without fracturing. The hardness of a material defines the resistance its surface opposes to penetration by an object such as an indenter. It is therefore a wear-resistant material. The hardness of cobalt-chrome is 360 HV. It is true that the hardness of 316L stainless steel, derived from a metal bar, is only 170 HV; but this hardness, after forging (the first stage of cup manufacturing), reaches 250 HV. It can therefore be said that the hardness of forged 316L stainless steel is close to that of cobalt-chrome. There is thus no significant difference. Stainless steel offers the advantage of being ductile. This property is particularly useful when one wishes to attach a fixation tab to a cup. Ductility allows the material to be deformed to adapt to the anatomy without breaking. This is not the case with cobalt-chrome. This ductility of stainless steel could lead to deformation at the equator during press-fit impaction, which is corrected by adding material.

Neither of these materials, cobalt-chrome or stainless steel, has good biocompatibility to allow for secondary fixation, which will necessitate an additional surface treatment. Forged 316L stainless steel provides all the necessary guarantees in terms of mechanical properties compared to the CoCrMo metal alloy, and it exhibits much better machinability qualities due to its ductility. The tribological capabilities of these materials actually depend only on the machining characteristics (surface roughness, Ra), a value that is too often, and wrongly, not communicated by manufacturers. It is the Ra value that will quantify the wear of the Polyethylene at the large-diameter articulation. It must be acknowledged that today the choice between cobalt-chrome and stainless steel is more of a marketing consideration than a reasoned physical one.

Due to the insufficient biocompatibility of these two materials, in the late 1990s, a hydroxyapatite (HA) surface treatment was often added directly onto cobalt-chrome or 316L stainless steel cups. There was a failure of all cobalt-chrome or 316L stainless steel cups coated with hydroxyapatite. For lack of secondary fixation, the medium-term results were unfavourable. These cups were abandoned. Since the work of Massin, it has been accepted that a titanium plasma spray coating applied to the body of a cup is the treatment of choice to allow for durable secondary fixation. To optimise the adhesion of the titanium to the metallic substrate, it is preferable to carry out this technology under a vacuum to minimise as much as possible the initiation points for delamination of the layers. The addition of an HA spray, according to the established principle, helps to accelerate the process of cup fixation to the healthy host bone.

The survival of such a system was studied in our department with a 10-year follow-up; this involved 350 patients who had a NOVAE SUNFIT® cup (Serf, Stryker) combined with a Corail stem (DePuy). The survival of the cup, for all causes, at 10 years is 98.6% [96.6%-99.4%].

Conclusion

After more than 45 years of existence, the dual mobility concept has established itself as a reliable and durable solution in total hip arthroplasty. What was originally a French innovation developed by Gilles Bousquet and André Rambert is now internationally recognised, with worldwide distribution and a constantly growing number of scientific publications.

Dual mobility, through its unique mechanical principle, offers a remarkable paradox: exceptional stability combined with an increased range of motion. This performance is confirmed by dislocation rates significantly lower than those of conventional prostheses, particularly with the posterior approach, where the dislocation risk is traditionally higher. The evolution of prosthetic design, from the original Tripod cup to symmetrical cylindro-spherical shapes, has optimised the "jumping distance" and improved the intrinsic stability of the system. The monobloc DMC (Dual Mobility Concept), representing the original French design, demonstrates superior biomechanical advantages over the MDM (Modular Dual Mobility) system, particularly in terms of stability and reduced risk of metal ion release.

Regarding materials, while the debate between 316L stainless steel and cobalt-chrome persists, it appears that the choice is driven more by marketing considerations than by genuine functional differences, as both alloys offer suitable mechanical properties when correctly machined. The titanium plasma spray surface treatment remains essential for ensuring durable secondary fixation.

The excellent clinical results, with survival rates exceeding 98% at 10 years in patients over 50, as well as the virtual absence of dislocations, confirm the relevance and durability of this concept. The elimination of intra-prosthetic dislocation, a specific complication of the early models, testifies to the constant improvements made to the system.

As Sir John Charnley predicted, the objective of a total hip prosthesis is "to build well for 20 years, and not for sensational short-term results". Dual mobility has not only achieved this objective but continues to evolve while preserving its fundamental principles, establishing itself as a benchmark in modern hip replacement surgery.

References

1. La double mobilité « en marche » dans les prothèses totales de hanche. Cahiers d’enseignement de la SOFCOT. Coordination : Michel-Henri Fessy et Denis Huten. 2018, Elsevier Masson