Choosing a treatment for hip dysplasia in 2024

Background: The management of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in adolescents and adults has evolved significantly, with a shift towards acetabular reorientation and arthroscopic techniques. However, selecting the optimal treatment from a wide array of non-surgical and surgical options remains a clinical challenge, necessitating clear guidance for surgeons on procedural indications.

Objective of the Article: This article provides a comprehensive overview of the diagnostic workup and therapeutic options for DDH, aiming to establish a clear framework for treatment selection based on clinical presentation, specific radiographic parameters, and the degree of osteoarthritis.

Key Points / Core Message: A precise diagnosis is foundational, requiring a thorough clinical examination and standardized radiographic evaluation, including AP pelvis, false profile, and Dunn views to measure key angles (VCE, VCA). Advanced imaging, such as arthro-CT, is indispensable for surgical planning. Treatment options range from non-operative management to complex hip-preserving surgery. Hip arthroscopy is reserved for borderline dysplasia (VCE 18-25°) and requires meticulous capsular and labral management. Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) is the gold standard for congruent, non-osteoarthritic hips. For non-congruent joints, severe dysplasia, or early osteoarthritis, salvage procedures like the Chiari osteotomy or, in select cases, bone block arthroplasty are indicated. Femoral osteotomies address associated deformities.

Conclusion / Implications for Practice: The treatment of DDH must be tailored to the individual patient. Acetabular reorientation via PAO offers the best outcomes for well-selected cases without significant osteoarthritis. In cases of incongruence or advanced dysplasia, salvage osteotomies like the Chiari are preferred. Total hip arthroplasty remains the solution for hips with advanced osteoarthritis (Tönnis grade 2-3).

Introduction

As imaging and surgical techniques have progressed, the management of hip dysplasia has become increasingly codified. Osteotomies around the femur and interventions to enlarge the hip have long been the mainstay of therapy. However, since the 1980s, the direction has been towards interventions to reorient the acetabulum and arthroscopic surgery. The aim of this work is to describe the different therapeutic options and to indicate which are the most appropriate.

Nosological framework

It is important to distinguish congenital dislocation of the hip, in which the hip is not engaged in the acetabulum in the uterus, from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), in which the abnormality occurs during development as the name suggests. It is this pathology that we will address here. DDH may follow on from congenital dislocation of the hip after it has been treated, but due to advances in childhood treatment, the majority of cases of dysplasia are identified during adolescence or adulthood. The early work of Wiberg (1939 paper) demonstrated that the severity of dysplasia, as defined by the VCE angle, was correlated with earlier symptoms and diagnosis at a younger age.

It is identified clinically, and the examination can provide a great deal of information.

The key symptom is pain, typically in the groin and sometimes the lateral hip. It usually arises at certain times of day and is of mechanical origin. Clinically, the hip is soft, in contrast to the picture in femoroacetabular impingement. Sometimes there is generalised laxity, which can be assessed using the Beighton score, with pain elicited on the FADIR, FABER or instability tests: pain provocation tests (pain on forced hyperextension and external rotation of the symptomatic hip with flexion of the contralateral hip) and AB-HEER test (pain on abduction, hyperextension and external rotation). More rarely dysplasia is identified due to limping or in an assessment for limb length discrepancy.

Diagnosis in women in late pregnancy or after delivery is very common and hip pain reported during this time should not be disregarded, erroneously attributed to weight gain. Instead, it should be assessed clinically and through plain radiographs.

The clinical examination can also indicate the severity of the condition and potential surgical options: a stiff hip (less than 90° of flexion, fixed flexion of 10° or more) suggests that there will be little room for hip-preserving management, especially if plain radiographs confirm osteoarthritis. Relief from pain when walking in abduction is a good indicator that a femoral varus reorientation osteotomy or acetabular reorientation will be successful (especially if improved congruence and greater joint space are observed on radiography in abduction). Finally, relief from pain while walking in adduction is a good indicator that a femoral valgus reorientation osteotomy will be successful (especially if improved congruence and greater joint space are observed on radiography in adduction).

Which imaging assessments should be performed? What should we look for and measure?

Diagnosis is confirmed by plain radiography, which should include:

- AP image of the pelvis

- False profile view of both hips (a good quality image is one taken standing and weight-bearing with the distance between the femoral heads corresponding to the diameter of one femoral head)

- Dunn view. This view has garnered support more recently due to the discovery of a frequent association between dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement. This association seems paradoxical since dysplasia leaves the femoral head less covered which should, in theory, free the hip, but in fact retroversion of the affected hip is not uncommon, and the same goes for a cam of the anterior femur.

The usual radiological definition involves a lateral coverage angle (VCE) < 25°, although the Ottawa team demonstrated that it is also important to take anterior coverage and, to a lesser degree, posterior coverage, into account as these findings can explain dysplasia symptoms in a hip with a normal VCE angle.

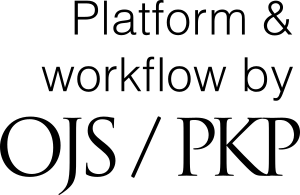

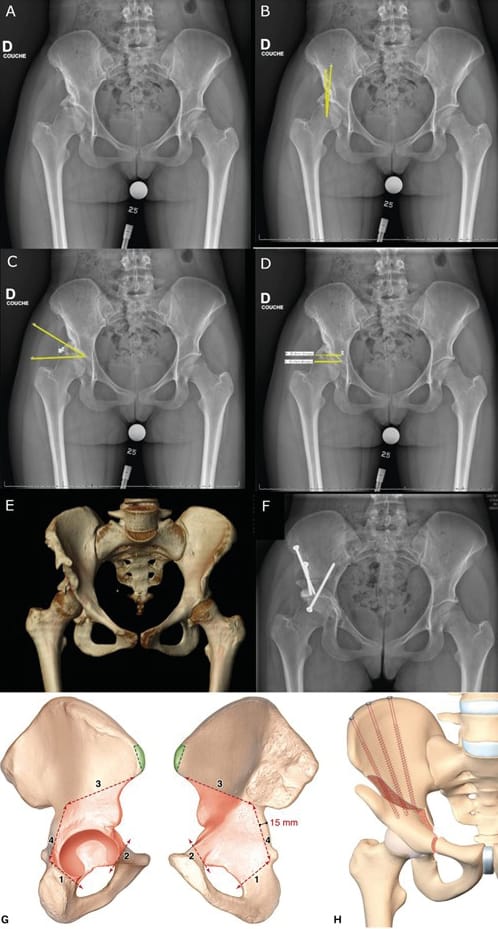

The following radiographic measurements are indispensable [1] Nwachukwu, B.U., et al., Arthroscopic Versus Open Treatment of Femo1. Tannast M, Hanke MS, Zheng G, Steppacher SD, Siebenrock KA. What are the radiographic reference values for acetabular under- and overcoverage? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015 Apr;473(4):1234–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-4038-3 (Figure 1):

- On the AP pelvic radiograph, the VCE is normal if ≥ 25°, borderline if between 20° and 25°, and dysplastic if < 20°, with severe dysplasia if VCE is < 0° (Figure 1C).

- On the false profile view, the VCA is normal if ≥ 25°, borderline if between 20° and 25°, and dysplastic if < 20°, with severe dysplasia if VCA is < 0° (Figure 1D).

- On the AP pelvic radiograph, the acetabular index, or Sharp angle, is normal if ≤10°, borderline if between 10° and 15°, and dysplastic beyond that. Severe forms are > 25° (Figure 1E)

- The Wagner index measures femoral head coverage (or, taking the opposite perspective, the femoral head extrusion index can be used): it is normal if > 80% (Figure 1F)

- Femoral neck-shaft angle: the NSA is normal between 125° and 135° (Figure 1G)

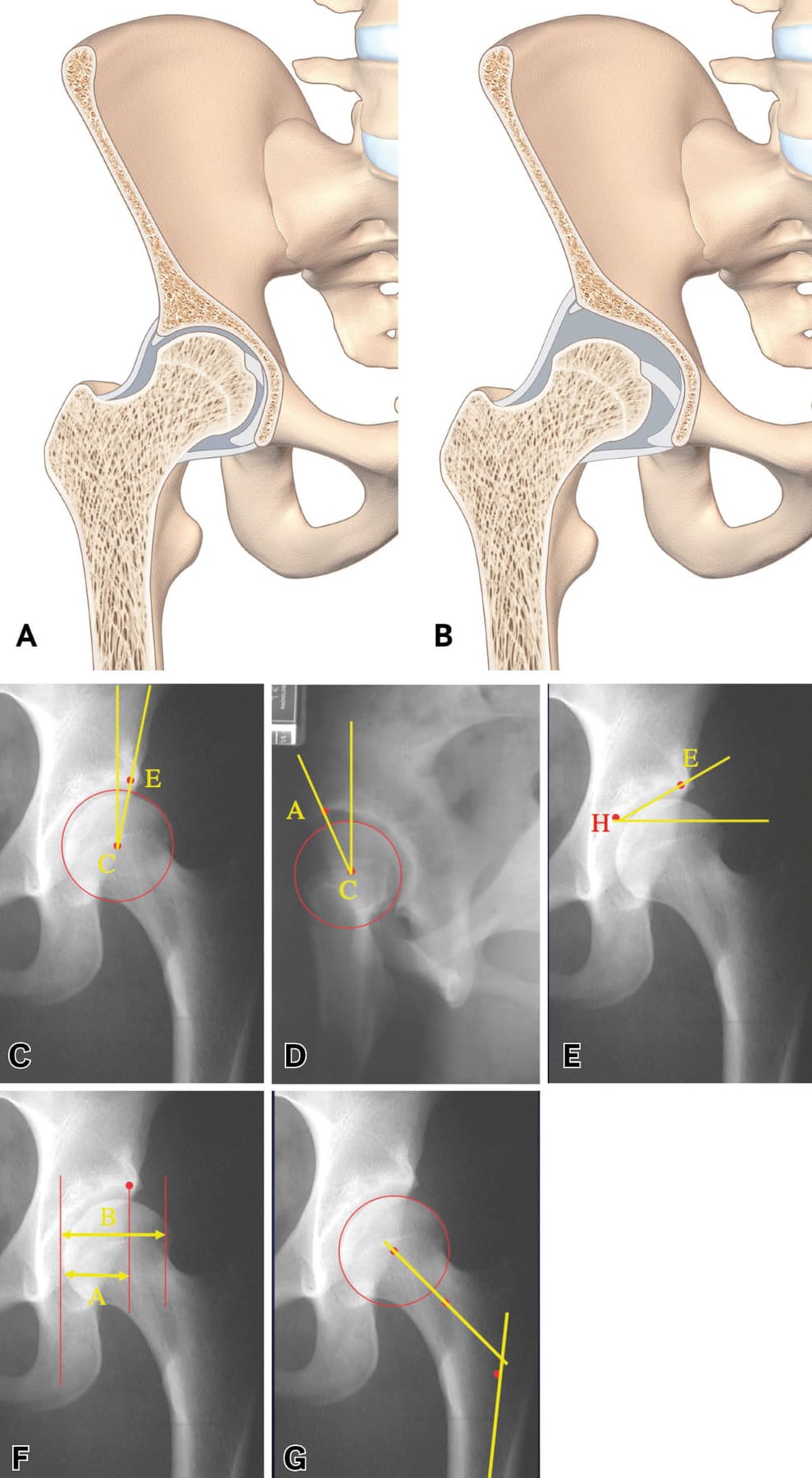

Tönnis classification of hip osteoarthritis (Figure 2):

- Grade 0: No sign of osteoarthritis.

- Grade 1: Early hip osteoarthritis: increased bone sclerosis, minimal joint space narrowing, absence or slight loss of femoral head sphericity.

- Grade 2: Moderate hip osteoarthritis: small bony cysts, moderate joint space narrowing, moderate loss of femoral head sphericity.

- Grade 3: Severe hip osteoarthritis: large bony cysts, severe narrowing or obliteration of the joint space, severe deformity of the femoral head.

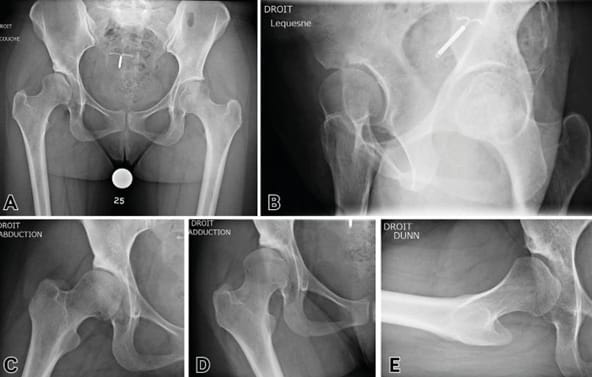

When an intervention is being considered, a number of radiographic investigations should be performed:

- AP view of hip in abduction: indispensable to estimate the joint space if planning acetabular reorientation and/or to predict repositioning in abduction if planning a femoral varus osteotomy (Figure 3).

- AP view of hip in adduction to estimate the joint space and repositioning if a femoral valgus osteotomy is planned where there is deformity of the femoral head with medial osteophyte formation.

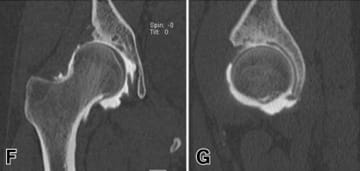

As it is no longer acceptable in 2024 to perform hip-preserving surgery in hip dysplasia without having contrast-enhanced CT images, the following are options:

- Arthro-CT, which is very accurate but uses more radiation than arthro-MRI (Figure 3). The advantage of arthro-CT is that labral lesions and thinning cartilage show up well. It should be preceded by a series of CT images without contrast material for 3D bone reconstruction, used to simulate the osteotomies and for the manufacture of custom cutting guides. CT can also be used to measure femoral anteversion, which may need a derotational osteotomy, as well as the AASA (anterior acetabular sector angle) and PASA (posterior acetabular sector angle).

- Arthro-MRI focuses on the functional, as it shows the painful areas of stress in the joint caused by intraosseous cysts. It is, however, less accurate than arthro-CT for imaging bone structures, which after all are the target for surgery. Unlike arthro-CT it does visualise cartilage flaps and detachment well.

Arthro-CT and MRI are often used by many teams to assess the condition of cartilage and labrum, but associated steps targeting these structures do not appear to improve the results of interventions to correct the dysplasia. Definitions of dysplasia based on angles appear to be less useful than 3D measurements, although they do act as the intraoperative guides for the correction based on the current condition, unless custom cutting guides are being used, as well as guides to measure displacement of the acetabular fragment if planning a reorientation.

If there is any query over the diagnosis, an intra-articular injection combining an anaesthetic and a steroid or a viscosupplementation injection may help to confirm that the hip is the origin of the symptoms.

Classifications

DDH is a broad spectrum of pathology that ranges from borderline dysplasia, in which radiographs could be interpreted as normal, to the hip that is prone to subluxation, especially following fracture of the acetabular rim. The Ottawa classification 2 can be used to determine the site of dysplasia when it is missed in the coronal plane and there is no dislocation. It is still based on plan film radiography. 3D reconstructions can help to improve the definition of the dysplasia although the data are difficult to apply perioperatively unless specific tools are available. The advantage of 3D measurements is that they confirm where dysplasia involves incorrect orientation but, more importantly, insufficient depth. For Verhaegen and Beaule 3 acetabular depth in asymptomatic hips is on average 22 ± 2mm, with cartilaginous joint surface of 2619 ± 415mm2 and 70% femoral head coverage. This is compared to 20 ± 4mm, mean difference 3mm [95% CI 1–4] (p < 0.001) and 67% ± 5% coverage for dysplastic hips, mean difference 6% [95% CI 0%–12%] (p = 0.03).

Treatment options

Non-surgical treatment

No comparative study has been able to demonstrate that surgical treatment is superior to physiotherapy and/or injections, although the literature lacks information on the non-surgical management of DDH.

Unequal limb length is the only circumstance in which there is convincing evidence for a non-surgical corrective treatment. When a patient has one shorter limb the contralateral hip becomes uncovered during walking. This leads to dynamic dysplasia, the symptoms of which can be treated by correcting the leg length discrepancy. This is also the case for hips affected by neurological disorders, in which spasticity resulting in excessive adduction can lead to undercoverage of the contralateral hip. Correcting excessive adduction and spasticity will correct the undercoverage. Finally, incorrect orientation due to lumbosacral joint arthrodesis producing posterior pelvic tilt leads to anterior undercoverage, which requires a specific strategy for correction.

Posture work/Physiotherapy: Posterior pelvic tilt leading to increased acetabular anteversion aggravates anterior undercoverage and the associated micro-instability. Posture work involves avoiding overextending the hip and knee and maintaining the axial position of the trunk when walking, and this can help to reduce the pain associated with DDH. Work to reduce step length may lead to a decrease in joint stress, and strengthening hip stabilisers may be suggested. Physiotherapy also addresses the management of associated periarticular pain (especially iliopsoas tendinitis) and rebuilding exercise tolerance.

Modifying activities: Sporting activities that involve hyperflexion, hyperextension and rotational stresses are associated with intra- and periarticular hip pathologies. It may be useful to advise a patient that they can address symptoms by reducing or modifying their sporting activities, avoiding deep flexion and internal rotation.

Intra-articular injections: There is no specific literature looking at the efficacy of intra-articular injections in hip dysplasia, but there are studies in painful pre-osteoarthritic hips that could be extrapolated. Steroid, hyaluronic acid or PRP injections could be offered, especially when there are early osteoarthritic lesions.

Arthroscopy

There is still debate over the place for arthroscopy in DDH among the community practising hip-preserving surgery [4] Lee MS, Owens JS, Fong S, Kim DN, Gillinov SM, Mahatme RJ, et al. Mid- and Long-Term Outcomes Are Favorable for Patients With Borderline Dysplasia Undergoing Primary Hip Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2023 Apr 1;39(4):1060–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.030. Early studies have produced mixed results, probably due to disruption to the hip stabilisers (capsulotomy without closure, labral debridement, excessive acetabuloplasty, psoas tenotomy, etc.) with failure rates ranging from 25 to 71% depending on the study. Evolving techniques, especially with labral repair/reconstruction and capsular plication, and improved patient selection (borderline dysplasia with VCE 18–25°) appear to produce satisfactory results with revision rates between 1.1 and 30%, depending on the study.

The risk factors for failure of isolated arthroscopy are dysplasia with VCE <18°, preoperative osteoarthritic lesions, older patients, excessive femoral anteversion, an absence of capsulorraphy, and labral debridement.

Arthroscopy can also be performed in combination with acetabular reorientation or bone block surgery. In Denmark it has been demonstrated that 11% of periacetabular osteotomies (PAO) subsequently require hip arthroscopy due to persistent pain (probably caused by a femoroacetabular impingement created by excessive displacement of the fragment or a persistent labral lesion), and one randomised study is currently ongoing to determine the value of arthroscopy combined with PAO.

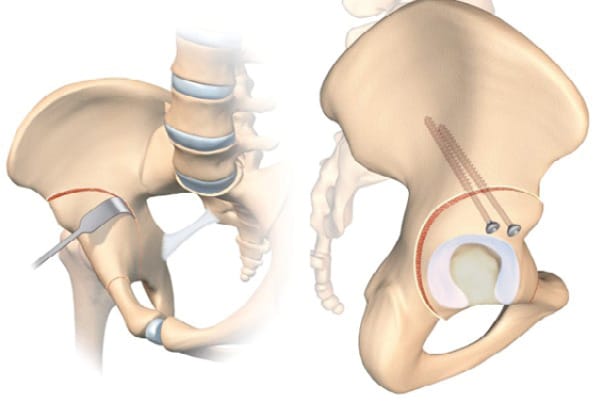

Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO)

Described by Ganz in 1988, this has become the gold-standard in hip-preserving surgery for DDH in North America and it is seeing increasing use in France [5] Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988 Jul;(232):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-198807000-00006 (Figure 5).

This is a surgical strategy for acetabular reorientation that preserves the posterior column, maintaining the stability of the pelvis and allowing the surgeon to avoid the reorientation challenges involving the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments.

The surgery involves four incisions:

- One partial incision to the ischium, around 1cm below the joint and under fluoroscopic guidance

- One to the pubic bone, close to the joint

- One above the acetabulum

- One to the posterior column starting from the supra-acetabular incision and heading towards the ischial incision.

The fragment is mobilised directly to achieve the rotation and then fixed with screws (4.5mm or 3.5mm), positioned from the iliac crest to the mobilised fragment without penetrating the joint.

This surgery is typically performed using the Smith–Petersen approach, which also allows for management of an associated femoroacetabular impingement, although minimally invasive approaches have been described, such as the trans-sartorius approach, which has the advantage of reducing the aesthetic impact and perioperative blood loss.

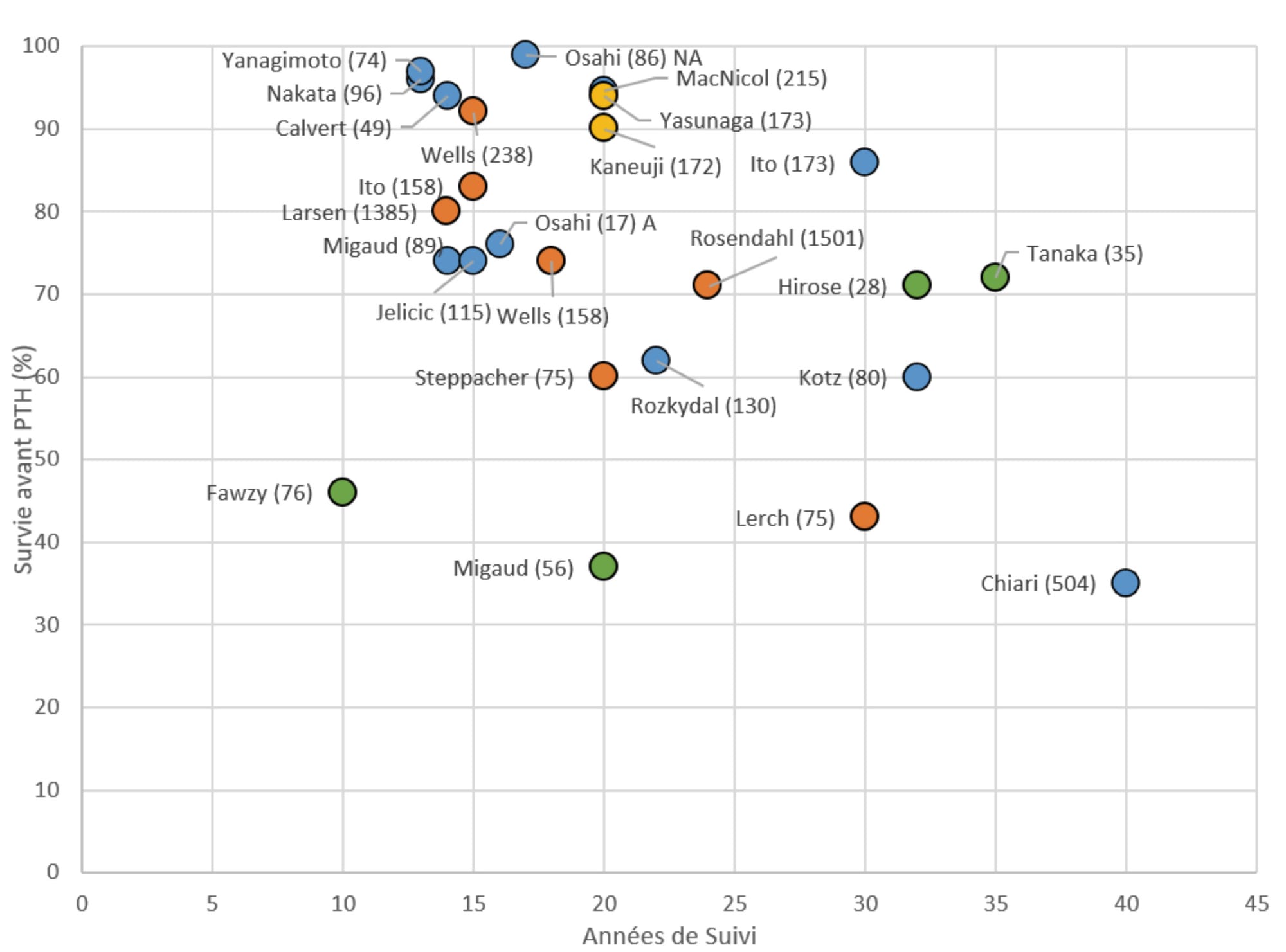

This is complex surgery at first sight, and it has a long learning curve. The rate of major complications can be high initially (18-36%) but training through mentoring seems to reduce this rate (1-6%). The main complications are non-union, infection, fracture of the posterior column and most importantly, sciatic nerve palsy, which is often irreversible. After over 15 years, survivorship without THA varies from one study to another, ranging from 43 to 92% with a notable 80% survival at 14 years in the Danish registry.

PAO is contraindicated in patients showing advanced osteoarthritis on radiography and when joint spaces are non-congruent unless it is combined with a procedure to reduce the femoral head. Obesity is a relative contraindication as complications are more common in this group (up to 30%), and as with every osteotomy, patients must be advised not to smoke.

Rotational acetabular osteotomy (RAO) is a technique initially described by Ninomiya and Tagawa in 1984, and it is another surgical strategy for acetabular reorientation, this time practised almost exclusively in Eastern Asia, and mainly in Japan [6] Yasunaga Y, Ochi M, Yamasaki T, Shoji T, Izumi S. Rotational Acetabular Osteotomy for Pre- and Early Osteoarthritis Secondary to Dysplasia Provides Durable Results at 20 Years. Clin Orthop. 2016 Oct;474(10):2145–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4854-8. It differs from PAO, with a spherical incision that does not disrupt the structure of the pelvic ring. A modified Smith–Petersen approach is used, which offers exposure of the anterior osteotomy in the interval between sartorius and tensor fasciae latae, as well as posteriorly, in a similar way to the Kocher–Langenbeck approach. The osteotomy is performed first with a motorised burr then with curved osteotomes under fluoroscopic guidance, avoiding releasing any fragments of acetabulum that are too fine (risk of necrosis) or creating a gap within the joint. The fragment is mobilised using a hook, fixed with screws and the osteotomy site is repaired with a cancellous bone graft (Figure 5). Another technique making use of a trochanteric osteotomy to improve visibility has been described.

The results seem to be excellent with over 90% survivorship without THA after 20 years in a Japanese population, although it remains to be confirmed whether corresponding results will be seen in a European population.

Complications are rare (0–18%) and consist mainly of acetabular necrosis, non-union, heterotopic ossification and nerve damage.

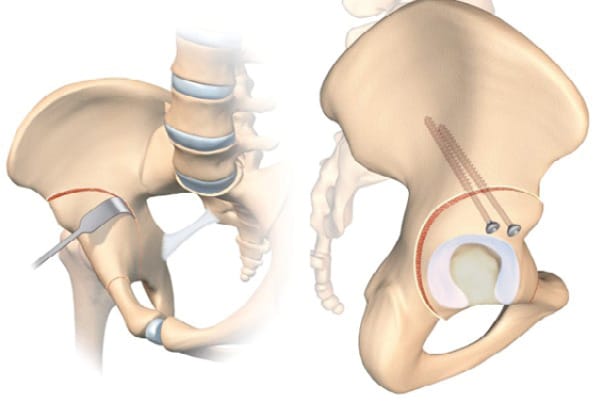

Bone block arthroplasty

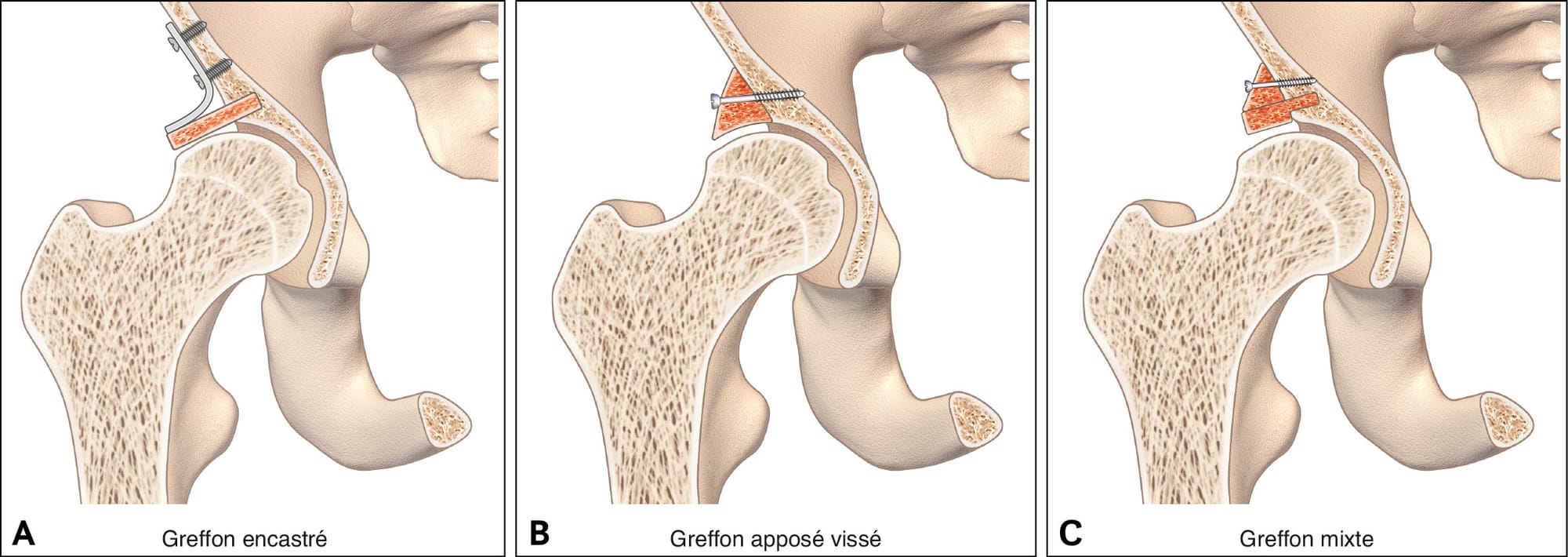

First described by König in 1891, the bone block technique has been adapted and modified by countless authors with an arthroscopic technique recently presented [7], Chiron P, Laffosse JM, Bonnevialle N. Shelf arthroplasty by minimal invasive surgery: technique and results of 76 cases. Hip Int 2007;17 Suppl 5:S72-82. https://doi.org/10.5301/hip.2008.1488[8] Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Jan;(418):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200401000-00014. It involves grafting a fragment of cancellous-cortical bone to the anterosuperior part of the acetabulum to improve bone coverage.

In contrast to the PAO or RAO this strategy increases the size of the acetabulum, similarly to the Chiari osteotomy, which involves metaplasia of the of the capsule and labrum to create a fibrocartilaginous interposition graft.

There are countless options for the approach route, with Smith–Peterson typically being used, although the Hueter anterior approach, minimally invasive medial approach described by Chiron and the Thaunat arthroscopic approach are all possible. The bone graft is taken from the exopelvic part of the iliac crest, and its size is determined preoperatively based on the desired correction. An incision is made at the anterosuperior part of the acetabulum, flush with the capsule, so that the bone block can be placed against the capsule and is stable without fixation. The fragment is then impacted until it is fixed well and/or fixed with screws and/or a plate.

The main complications are lysis of the graft and non-union.

Results have been mixed with 46% survivorship without THA for Fawzy et al and 37% after 20 years in our facility. This is in contrast to Japanese studies with over 70% survivorship with 30 years of follow-up. These results are, however, difficult to compare to those of PAO or RAO because they are used in different populations. In the bone block studies, the largest portion of the population are patients with osteoarthritis, while the advent of modern pelvic osteotomies has been more recent, meaning patient selection has improved, and consequently so have the clinical results. If we look at bone block in the absence of osteoarthritis and subluxation, the survival rate is 81% after 21 years of follow-up [8] Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Jan;(418):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200401000-00014. However, this is a salvage strategy for extremely subluxed or even dislocated hips in which neither PAO nor RAO is possible, nor Chiari osteotomy in view of the risk of the line ending in the sacroiliac joint, preventing medialisation (Figure 6).

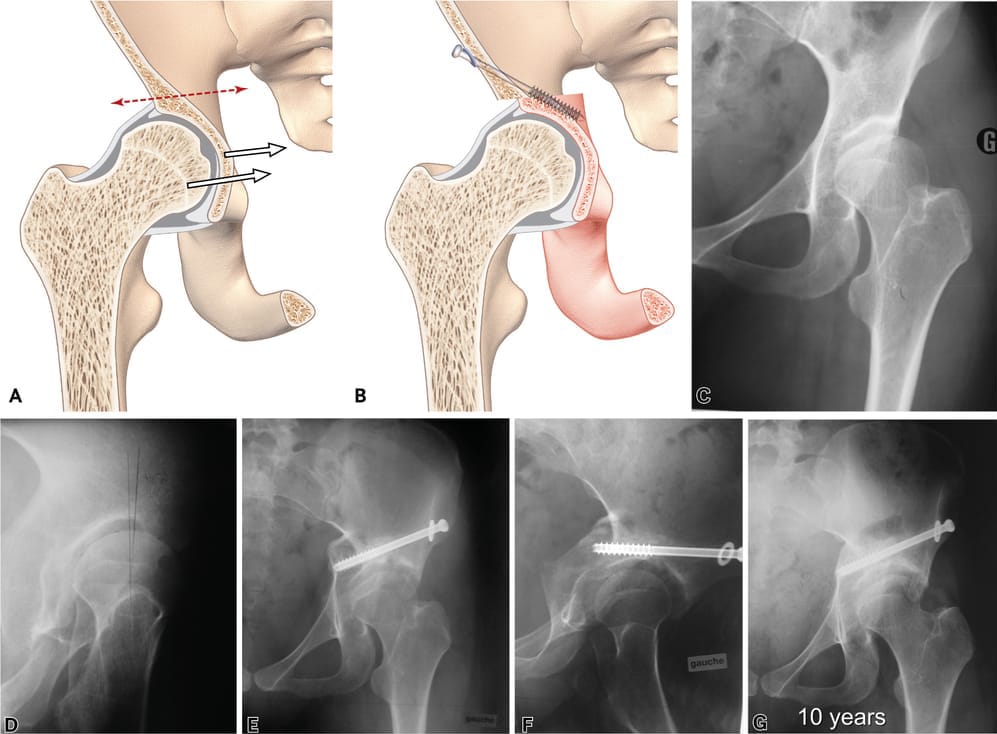

Chiari osteotomy

The Chiari osteotomy was described in 1953. This is an extra-articular dome osteotomy [8], Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Jan;(418):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200401000-00014[9], Chiari K. Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974 Jan-Feb;(98):55-71. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197401000-00008. PMID: 4817245.[10] Chiari C, Schneider E, Stamm T, Peloschek P, Kotz R, Windhager R. Ultra-long-term results of the Chiari pelvic osteotomy in hip dysplasia patients: a minimum of thirty-five years follow-up. Int Orthop. 2024 Jan;48(1):291-299. doi: 10.1007/s00264-023-05912-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-023-05912-9 that follows the contour of the femoral head to medialise the centre of rotation of the joint and increase the acetabular surface (Figure 7). As with the bone block, this osteotomy above the acetabulum uses capsular metaplasia with fibrocartilaginous tissue, but the medialisation produced decreases the lever arm of the joint and therefore intra-articular stresses.

This strategy usually begins with the Smith–Petersen approach and a single osteotomy incision above the acetabulum, oriented cranially from the outside inwards under fluoroscopic guidance, and following the contour of the femoral head. At the planning stage, it is important to make sure that the osteotomy will end below the sacroiliac joint, or it will not be possible to mobilise the distal fragment. The new positioning is achieved by placement in abduction and fixation with a 6.5mm screw. The main complications described, though certainly rare, are nerve damage (sciatic nerve) and non-union. Functional outcomes are good, with survivorship over 70% after 15 years (74–97%), 60–85.9% after 30 years and 35% survivorship after 40 years in Chiari’s original series. This technique is not especially sensitive to deformity of the femoral head, subluxation or osteoarthritis if dysplasia is severe with negative VCE and VCA (< 0°) (Figure 8).

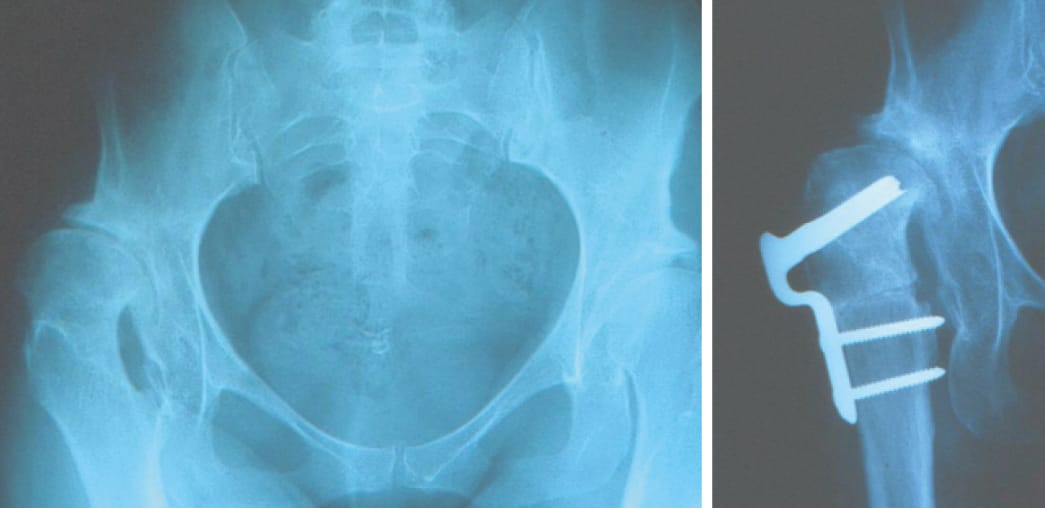

Femoral osteotomy

Historically in cases of DDH associated with femoral valgus, a femoral varus osteotomy may have been offered, however this can complicate a subsequent THA, especially if it leads to translation or an issue with rotation. With the advent of acetabular reorientation strategies, femoral osteotomy finds its indication in combination with acetabular reorientation due to fovea alta (reducing the cartilaginous contact surface), poor congruence or a tilt defect, or as a salvage strategy (Figure 9). Thorough planning is required and fixation can be achieved with a locked plate or blade plate, with the advantage of the latter being that they are low-cost and the fixed angle makes planning straightforward.

How to choose a treatment

We suggest that if it has not yet been done, intra-articular injection and physiotherapy should be tried. This will confirm whether symptoms originate from the hip, prepare the patient for surgery both in terms of strengthening muscle and mental readiness and it will demonstrate that the issue is resistant to medical treatment correctly followed. We believe it is preferable to offer arthroplasty to Tönnis grade 2 and 3 patients, but in some exceptional cases, such as very young patients, conservative management can be discussed only when dysplasia is very severe (VCE and VCA <<0°).

In DDH without subluxation and/or with repositioning on the abduction image and no osteoarthritis, the best choice is acetabular reorientation, as long as this procedure has been mastered, the hip is mobile and congruence is improved on imaging of repositioning. Since RAO has only been validated in Asian populations, we perform PAO as this has the benefit of a less invasive approach. However, when a hip is non-congruent this technique is contraindicated (unless it is combined with an osteotomy to reduce the femoral head, a technically complicated and risky procedure) so the choice will be between a Chiari osteotomy and bone block. The Chiari osteotomy is undoubtedly more difficult but it gives better results in the long term, and this is why we prefer it (Figure 10). It is also less sensitive than bone blocks to osteoarthritis and subluxation, in cases of severe dysplasia. Bone block is the more straightforward technique but it is less effective when there is osteoarthritis and/or subluxation, so its indications have greater overlap with PAO and RAO. In patients with moderate acetabular dysplasia, excess anteversion and valgus femur, our strategy is firstly a femoral varising derotation osteotomy, associated with a step to address the acetabulum if necessary, once the more straightforward femoral step has been completed.

An arthroscopic strategy to manage femoroacetabular impingement in a borderline dysplastic hip could be offered but the technique must be performed rigorously and include labral repair and capsulorraphy.

References

1. Nwachukwu, B.U., et al., Arthroscopic Versus Open Treatment of Femo1. Tannast M, Hanke MS, Zheng G, Steppacher SD, Siebenrock KA. What are the radiographic reference values for acetabular under- and overcoverage? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015 Apr;473(4):1234–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-4038-3

2. Bali K, Smit K, Ibrahim M, Poitras S, Wilkin G, Galmiche R, et al. Ottawa classification for symptomatic acetabular dysplasia assessment of interobserver and intraobserver reliability. Bone Joint Res 2020 Jun 8;9(5):242–9. https://doi.org/10.1302/2046-3758.95.bjr-2019-0155.r1

3. Verhaegen JCF, DeVries Z, Rakhra K, Speirs A, Beaule PE, Grammatopoulos G. Which Acetabular Measurements Most Accurately Differentiate Between Patients and Controls? A Comparative Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2024 Feb 1;482(2):259-274. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002768. https://doi.org/10.1097/corr.0000000000002768

4. Lee MS, Owens JS, Fong S, Kim DN, Gillinov SM, Mahatme RJ, et al. Mid- and Long-Term Outcomes Are Favorable for Patients With Borderline Dysplasia Undergoing Primary Hip Arthroscopy: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2023 Apr 1;39(4):1060–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.030

5. Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988 Jul;(232):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-198807000-00006

6. Yasunaga Y, Ochi M, Yamasaki T, Shoji T, Izumi S. Rotational Acetabular Osteotomy for Pre- and Early Osteoarthritis Secondary to Dysplasia Provides Durable Results at 20 Years. Clin Orthop. 2016 Oct;474(10):2145–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4854-8

7. Chiron P, Laffosse JM, Bonnevialle N. Shelf arthroplasty by minimal invasive surgery: technique and results of 76 cases. Hip Int 2007;17 Suppl 5:S72-82. https://doi.org/10.5301/hip.2008.1488

8. Migaud H, Chantelot C, Giraud F, Fontaine C, Duquennoy A. Long-term survivorship of hip shelf arthroplasty and Chiari osteotomy in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Jan;(418):81–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200401000-00014

9. Chiari K. Medial displacement osteotomy of the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974 Jan-Feb;(98):55-71. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197401000-00008. PMID: 4817245.

10. Chiari C, Schneider E, Stamm T, Peloschek P, Kotz R, Windhager R. Ultra-long-term results of the Chiari pelvic osteotomy in hip dysplasia patients: a minimum of thirty-five years follow-up. Int Orthop. 2024 Jan;48(1):291-299. doi: 10.1007/s00264-023-05912-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-023-05912-9

11. Migaud H, Putman S, Berton C, Lefèvre C, Huten D, Argenson JN, Gaucher F. tDoes prior conservative surgery affect survivorship and functional outcome in total hip arthroplasty for congenital dislocation of the hip? A case-control study in 159 hips. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014 Nov;100(7):733-7. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.016 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2014.07.016