Acetabular reconstruction with custom 3D-printed implants: surgical technique and report of experience

Background / Problem: Management of severe acetabular bone loss (Paprosky type IIIA/B, IV) and pelvic discontinuity presents a formidable challenge in revision total hip arthroplasty (THA). While porous metal modules are effective for moderate defects, they often suffice poorly for massive defects or discontinued anatomy, necessitating more tailored reconstructive solutions.

Objective of the Article: This study reports on a ten-year experience (2011–2021) comprising 68 cases to define the surgical indications, technical principles, and clinical outcomes of using custom 3D-printed titanium implants for complex acetabular revisions.

Key Points / Core Message: Utilizing Electron Beam Melting (EBM) technology and preoperative CT planning, the authors developed specific protocols for implant generation. The surgical technique prioritizes achieving primary uncemented press-fit fixation—specifically equatorial or craniocaudal anchorage—to ensure biological integration. The authors propose a decision-making algorithm based on the feasibility of this press-fit. Implants were consistently paired with cemented dual-mobility (DM) cups to mitigate instability, a primary complication observed (20% in the initial series). Notably, the study validates the use of these implants in septic revisions, reporting successful outcomes in one-stage exchange procedures for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) comparable to aseptic cases. Immediate full weight-bearing was achieved in 90% of patients.

Conclusion / Implications for Practice: Custom 3D-printed implants offer a robust, viable solution for massive acetabular defects and pelvic discontinuity where standard modular options fail. Clinical success is contingent upon rigorous 3D planning, achieving press-fit stability, and the correct concomitant use of dual-mobility constructs to prevent dislocation.

Introduction

Over the course of a decade, porous metal acetabular reconstructions have found their place in the treatment arsenal for acetabular revisions to the point that they are considered a credible alternative to the gold standard, porous metal cages with cemented dual mobility implants. Where there are more significant defects, which push the limits of standard reconstruction techniques, custom implants produced using additive manufacturing (with titanium powder) can be applied in the same indications as modular implants or even Triflange components (whether custom-made or not).

Although the literature is starting to show clinical results and medium-term survival data, there remains a lack of information on the specific features of these surgical procedures in daily practice. Yet, this information governs correct usage of implants and the quality of outcomes.

In practice, there are a number of rules, principles and technical points that must be applied: they should only be used in certain indications, planning must anticipate potential issues and above all the surgical procedure must follow appropriate steps to reduce implantation failures and iatrogenic complications.

Twelve years of use in both aseptic and septic revisions (performed either as one or two-stage procedures) means we are well-positioned, as a team who have developed this technique, to share our practical experience and offer a basis for further reflection on the prevention or management of both predictable and less usual complications.

Porous metal reconstructions - what implants are available?

Where there is massive bone loss, especially if there is concomitant pelvic discontinuity, the standard technique of bone grafting with primary cemented fixation with or without a cage has demonstrated its limitations with primary fixation failures or a lower 10-year survival rate.

Alternatives developed over the past decades consist of reconstructions using porous metals that promote bone ingrowth or ongrowth. The literature on this topic is sparse and any published case series has a limited follow-up period, usually under 5 years, and low case numbers [1], Aprato A, Giachino M, Bedino P, Mellano D, Piana R, Massè A. Management of Paprosky type three B acetabular defects by custom-made components: early results. Int Orthop. 2019;43(1):117-122. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-4203-5[2], Burastero G, Cavagnaro L, Chiarlone F, et al. Clinical study of outcomes after revision surgery using porous titanium custom-made implants for severe acetabular septic bone defects. Int Orthop. 2020;44(10):1957-1964. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04623-9[3], Gruber MS, Jesenko M, Burghuber J, Hochreiter J, Ritschl P, Ortmaier R. Functional and radiological outcomes after treatment with custom-made acetabular components in patients with Paprosky type 3 acetabular defects: short-term results. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):835. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-03851-9[4] Perticarini L, Rossi SMP, Benazzo F. Trabecular titanium tailored implants in complex acetabular revision surgeries: our experience at minimum 3 years follow-up. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(5 Suppl. 1):45-49. IORS Special Issue on Orthopedics..

Migaud [5] Migaud H, Common H, Girard J, Huten D, Putman S. Acetabular reconstruction using porous metallic material in complex revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(1S):S53-S61. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2018.04.030 carried out a systematic literature review of these porous metals and the implants made from them.

The materials explored were Trabecular MetalTM (TM), Trabecular TitaniumTM, TritaniumTM, ConcelocTM, RegenererexTM and GriptionTM. TM is the only one that has been investigated in a significant number of publications, and these have highlighted several points: instability is the main cause of revision of TM implants not fitted with a dual mobility component, and the first three materials listed above are the ones recommended for use in this way. The second reservation is the 10-year survival rate of these implants: the literature provides evidence on this point for Trabecular Metal only. By contrast, registry data are less clear and do not show TM to have any advantage over titanium. Finally, the low infection rate with Tantalum suggests that this material may have a preventive effect, yet this was not confirmed when compared to titanium in a study into biofilm formation [6], Tokarski AT, Novack TA, Parvizi J. Is tantalum protective against infection in revision total hip arthroplasty? Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(1):45-49. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B1.34236[7] Laaksonen I, Lorimer M, Gromov K, et al. Does the Risk of Rerevision Vary Between Porous Tantalum Cups and Other Cementless Designs After Revision Hip Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(12):3015-3022. doi:10.1007/s11999-017-5417-3.

The implants developed with these materials fall into two types:

- Modular implants with no need for 3D planning, with or without the use of cemented wedges [8], Moličnik A, Hanc M, Rečnik G, Krajnc Z, Rupreht M, Fokter SK. Porous tantalum shells and augments for acetabular cup revisions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(6):911-917. doi:10.1007/s00590-013-1354-3[9] Konan S, Duncan CP, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Porous tantalum uncemented acetabular components in revision total hip arthroplasty: a minimum ten-year clinical, radiological and quality of life outcome study. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(6):767-771. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.37183.

- Custom-made implants: four are currently on the market (MaterialiseTM 2009, Lima custom-made Trabecular TitaniumTM 2007, Adler custom-made Ti-porTM 2010, SERF ARM with surface that promotes bone ingrowth 2016). A fifth option that must be added is the Gruppo Bioimplanti CustoMizedTM. Just a few publications have provided follow-up information on these implants, with survival rates for the first four ranging from 88.5% at 54 months to 100% at 67 months [5] Migaud H, Common H, Girard J, Huten D, Putman S. Acetabular reconstruction using porous metallic material in complex revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(1S):S53-S61. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2018.04.030.

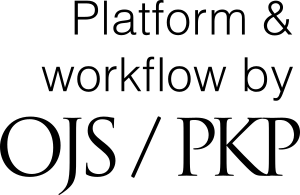

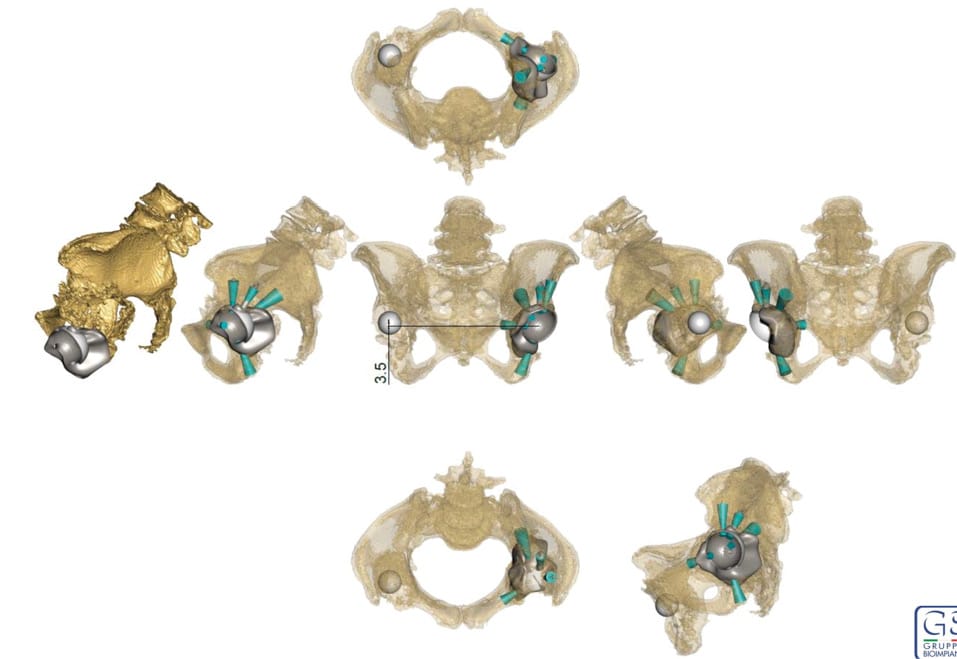

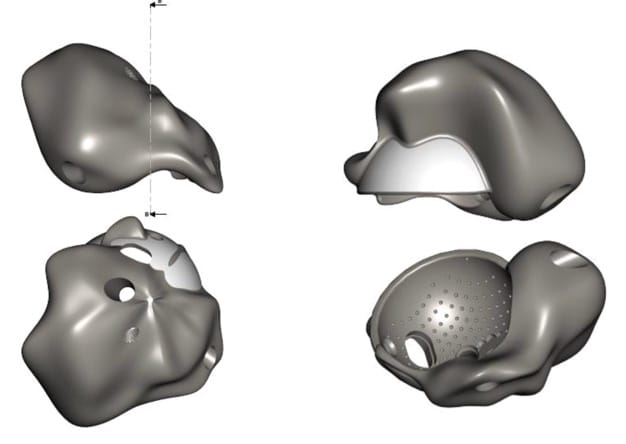

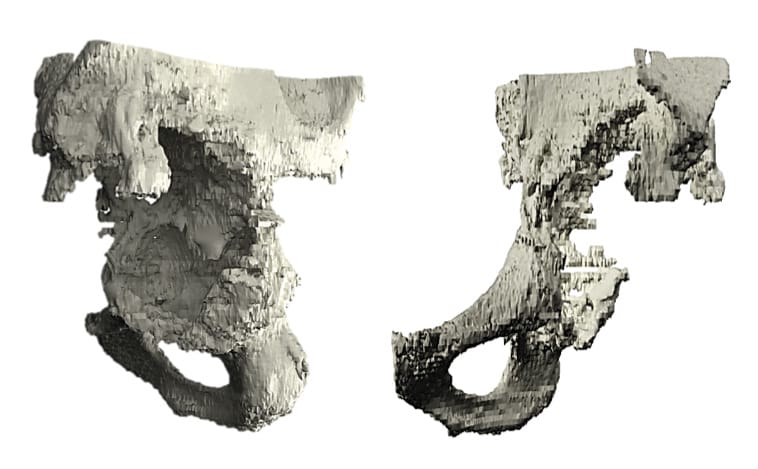

This article focuses on custom implants produced from titanium powder using additive manufacturing. (Figures 1 & 2)

Indications

The basis for the experience we report is 68 implants fitted between 2011 and 2021. This activity accounted for around 6% of our indications for revisions over this period. This percentage is not insignificant and it shows that management of major acetabular bone loss is not at the margins of what we consider to be standard revision. It is becoming central in the treatment of failed primary revisions, which corresponds to the majority of patients discussed here.

A first and fundamental point is that we should not extend application beyond the established field of use for these implants. We must avoid discrediting these components by looking at the current and future challenges; changes in regulations concerning production, use and reimbursement. The indications must remain restricted to the most complex cases of bone loss.

Which defects can be treated?

In our experience, we only treated cases of major bone loss, in which the acetabulum was at least compromised or even discontinuous. There are three classifications used to grade these bone defects: Paprosky [10] Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9(1):33-44. doi:10.1016/0883-5403(94)90135-x, AAOS [11] Ahmad AQ, Schwarzkopf R. Clinical evaluation and surgical options in acetabular reconstruction: A literature review. J Orthop. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S238-S243. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.011 and Saleh [12] Saleh KJ, Jaroszynski G, Woodgate I, Saleh L, Gross AE. Revision total hip arthroplasty with the use of structural acetabular allograft and reconstruction ring: a case series with a 10-year average follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):951-958. doi:10.1054/arth.2000.9055. A preoperative CT scan is performed as a matter of routine for the 3D planning needed to produce the implant. In practice, for our first 30 cases:

- On the Paprosky classification, all patients presented a severe bone defect: type IIIA for 39.2%, type IIIB for 35.7% and type IV for 10.7%. Seven patients had pelvic discontinuity with a type IIIA or IIIB defect. Three defects were type IIA, and one was type IIB.

- Applying the AAOS classification, 55.5% had bone loss that met the criteria for a type III defect, 25.9% a type IV defect and 11.1% a type V defect.

- On the Saleh classification, 32.1% had bone loss that fitted type III, 39.3% type IV and 21.4% type V.

Evaluation of acetabular bone loss: Do these classifications help us to plan surgery and manufacture the right implant?

Whether the classifications are “anatomical”, based on a description of well-known radiological acetabular landmarks, “volumetric” in that they look at the percentage of bone stock remaining, or “analytical”, extrapolating bone loss by analysing the migration of the acetabular component, all three are judged to offer poor reliability and reproducibility [13], Gozzard C, Blom A, Taylor A, Smith E, Learmonth I. A comparison of the reliability and validity of bone stock loss classification systems used for revision hip surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):638-642. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00107-4[14] Aprato A, Olivero M, Di Benedetto P, Massè A. Decision/therapeutic algorithm for acetabular revisions. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(14-S):e2020025. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10999. The Saleh classification is probably the most reliable and the only one that has demonstrated interobserver reproducibility. It evaluates the percentage of residual bone in contact with the implant and aims to predict how the component to be implanted will integrate with the remaining bone stock [15] Johanson NA, Driftmier KR, Cerynik DL, Stehman CC. Grading acetabular defects: the need for a universal and valid system. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(3):425-431. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.02.021.

A preoperative cross-referenced analysis of acetabular bone loss aimed to determine whether any one classification or combination of classifications would prove to stand out as useful in predicting the true picture of perioperative defects and planning the fixation type.

In our experience, while these classifications proved to be useful and fairly reliable for anticipating situations that arose during surgery, they tended to overlook the additional bone loss generated by the extraction of an implant that is not loosened and/or by bone debridement, especially in cases with acetabular osteitis. On this last point, the majority of cases of osteitis consisted of cavitary defects. Then, the preoperative defect classification was not amended even though these defects were always made worse by the debridement and ablation of implants.

In practice: the bone loss found perioperatively did not differ from the type anticipated. Only segmental bone loss in osteitis could in theory affect the quality of the planned fixation and therefore cause the implantation to fail.

In all cases, for the planned fixation to coincide with the true picture perioperatively it is crucial to follow the principles of planning, extraction and debridement that we will set out.

Design - Planning - Manufacturing the implant

Beyond the classifications, use of these implants must prompt us to adopt a perspective that focuses on “remaining bone volume” rather than bone loss, and to relate this volume to the intended primary anchoring.

These volumes fall into two geometric types:

- Those that are an approximate hemisphere that can be held at the “equator”

- Those that are more complex, in which the acetabulum is non-continuous: in these cases, the planning must configure anchoring based on different criteria. Anchoring points at the anterior and posterior columns and in the roof of the acetabulum will need to be planned, without necessarily looking to completely fill the volume of the defect.

The planning must take into account both:

- Whether there is acetabular discontinuity

- Whether the “equator” is continuous

- And look for anchoring points in the three areas mentioned above. These last points are fundamental for the surgical validation of our engineering colleagues’ proposed planning, and also perioperatively when adjusting the implant positioning.

In practice: The planning must be used to look for primary fixation through a press-fit at three points, or as a minimum at two points that are directly opposite each other, rather than relying on a hanging effect to fix the whole of the surface. This “rule” was drawn from observation, and supports conclusions made by Macák [16] Macák D, Džupa V, Krbec M. [Custom-Made 3D Printed Titanium Acetabular Component: Advantages and Limits of Use]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2021;88(1):69-74.. However, it is important to limit residual dead space and seek satisfactory filling without “sticking” to the geometry of the bone loss for two reasons:

- If there is too much dead space, this could potentially lead to recurrence of infection where an inoculum persists (especially if the procedure if performed in a single intervention) or infection of the site.

- If the geometry of an implant is too complex, it may be difficult to fit it due to the effects of premature contact with bony prominences that has been poorly evaluated in the planning stage. In our experience metal artefacts on CT did not result in insurmountable gaps between the “planned” and the perioperative anchoring, but they may explain these perioperative difficulties. This means that in cases with these kinds of geometries, the implant design must take the configuration into account and smooth out any unnecessary and interfering relief.

By cross-referencing experiences of fitting implants, classifications, volumetric and geometric factors, we have created an algorithm for using a press-fit implant, set out later on.

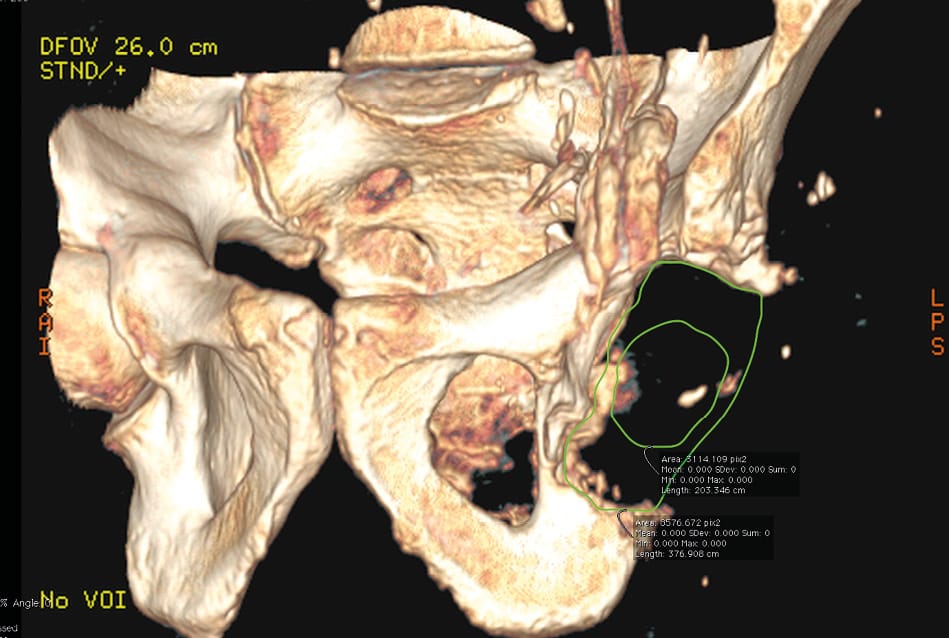

The manufacturing process used is Electron Beam Melting (EBM technology). The whole process takes on average 6-7 weeks, and includes four steps:

- A CT scan of the acetabulum is performed that uses slices maximum 2mm thick and 3D bone reconstruction focusing on the part to be reconstructed and the neighbouring area.

- The data are sent to the manufacturer's R&D department (through an FTP server or on a DVD) and the relevant anatomical segments are reconstructed in 3D.

- In 3 weeks, a virtual implant is offered to the surgeon in 3D (through access to a secure website)

- Within 4 weeks the implant is manufactured and delivered.

Unlike with modular implants, the custom manufacture does entail a lead time. It takes an average of 6-7 weeks from approval of the project to delivery of the implant. The CT acquisition protocol was simple to set up and there was no major inconsistency noted between the planning, the implant delivered and its positioning, which supports the conclusions of other teams [17], Baauw M, van Hellemondt GG, van Hooff ML, Spruit M. The accuracy of positioning of a custom-made implant within a large acetabular defect at revision arthroplasty of the hip. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):780-785. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B6.35129[18] Zampelis V, Flivik G. Custom-made 3D-printed cup-cage implants for complex acetabular revisions: evaluation of pre-planned versus achieved positioning and 1-year migration data in 10 patients. Acta Orthop. 2021;92(1):23-28. doi:10.1080/17453674.2020.1819729 In two cases, the manufacture was delayed and this meant the surgery had to be postponed for a week.

In two cases out of the two-stage procedures, a cement imprint was made during the first intervention. This was then compared to the data from the CT scan performed between the two interventions. These were cases with complex bone loss, which required cementing in the second intervention. This technique does not necessarily offer more than 3D reconstruction and cannot be substituted for it. From our perspective, 3D planning is sufficient and making an imprint or using a phantom does not offer added value.

Features of the surgical technique

Approach route adaptations

Using these implants does not affect the approach routes chosen for revisions. A posterolateral approach route that mirrored the route of the original surgery, either extended or not, was always used. A proximal extension may prove to be necessary if there is very significant bone loss at the acetabular roof, particularly if the planning determined that a proximal plate should be used. In bipolar revisions, a femorotomy as needed allows for optimum exposure and must be performed before the acetabular component is removed.

If only the acetabulum is being revised and the femoral implant is remaining in place, it may prove to be necessary to expose the acetabulum, especially if there is stiffness and retraction, and to combine arthrolysis of the hip and femur with expanding the distal aponeurosis of gluteus maximus which means that the femur can be projected forward and up (reinserted at the end of surgery).

In septic revisions, any fistula outside the incision or at an anterior route was treated at the same time without changing this approach strategy. Antibiotic therapy was started as soon as specimens were taken. A grinding technique with a sampling kit was always used for microbiology, and this was routinely completed by samples taken for histopathology.

Explantation - Debriding the acetabulum

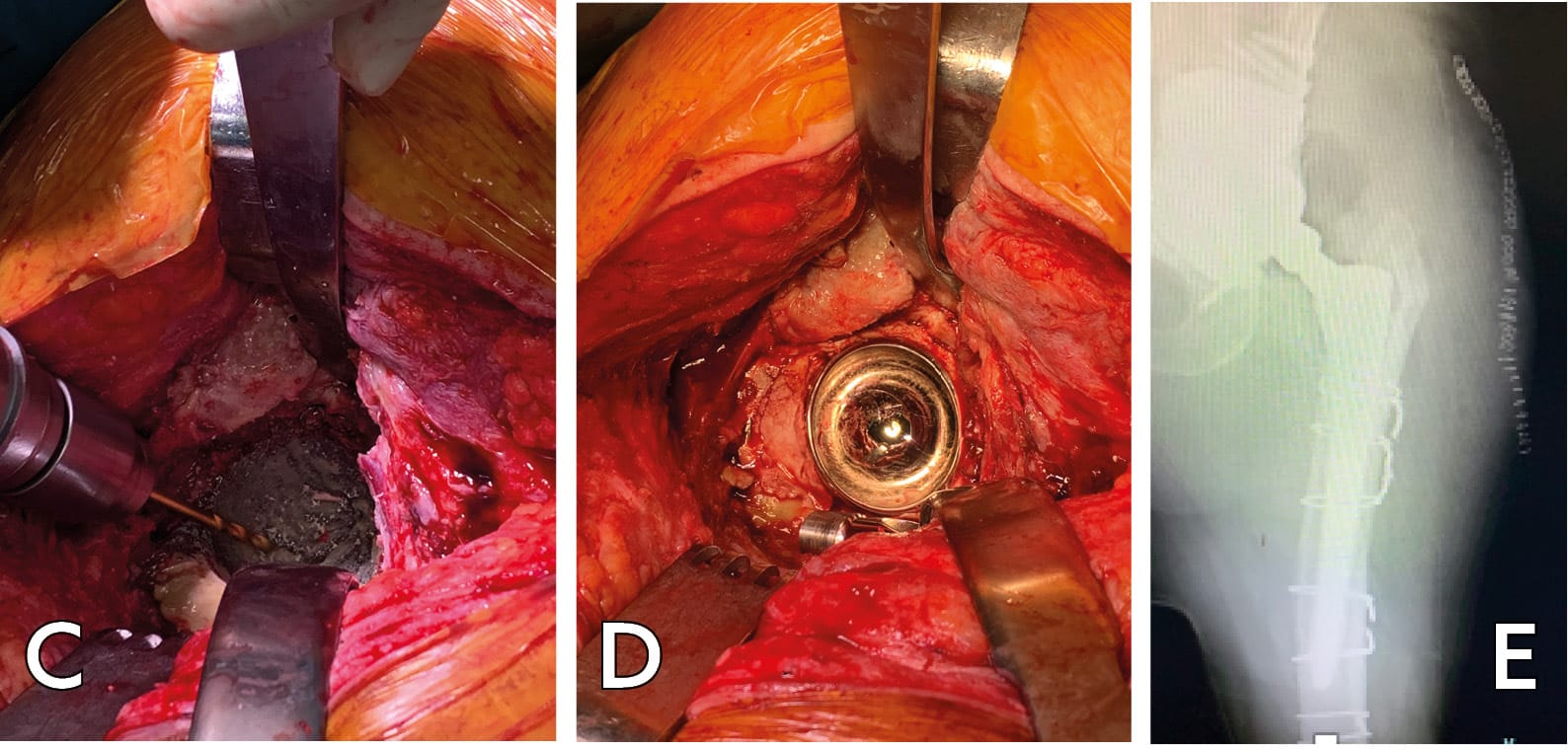

If there is no loosening of the acetabular component, explantation of the primary acetabular implant is always done manually using a Cauchoix osteotome.

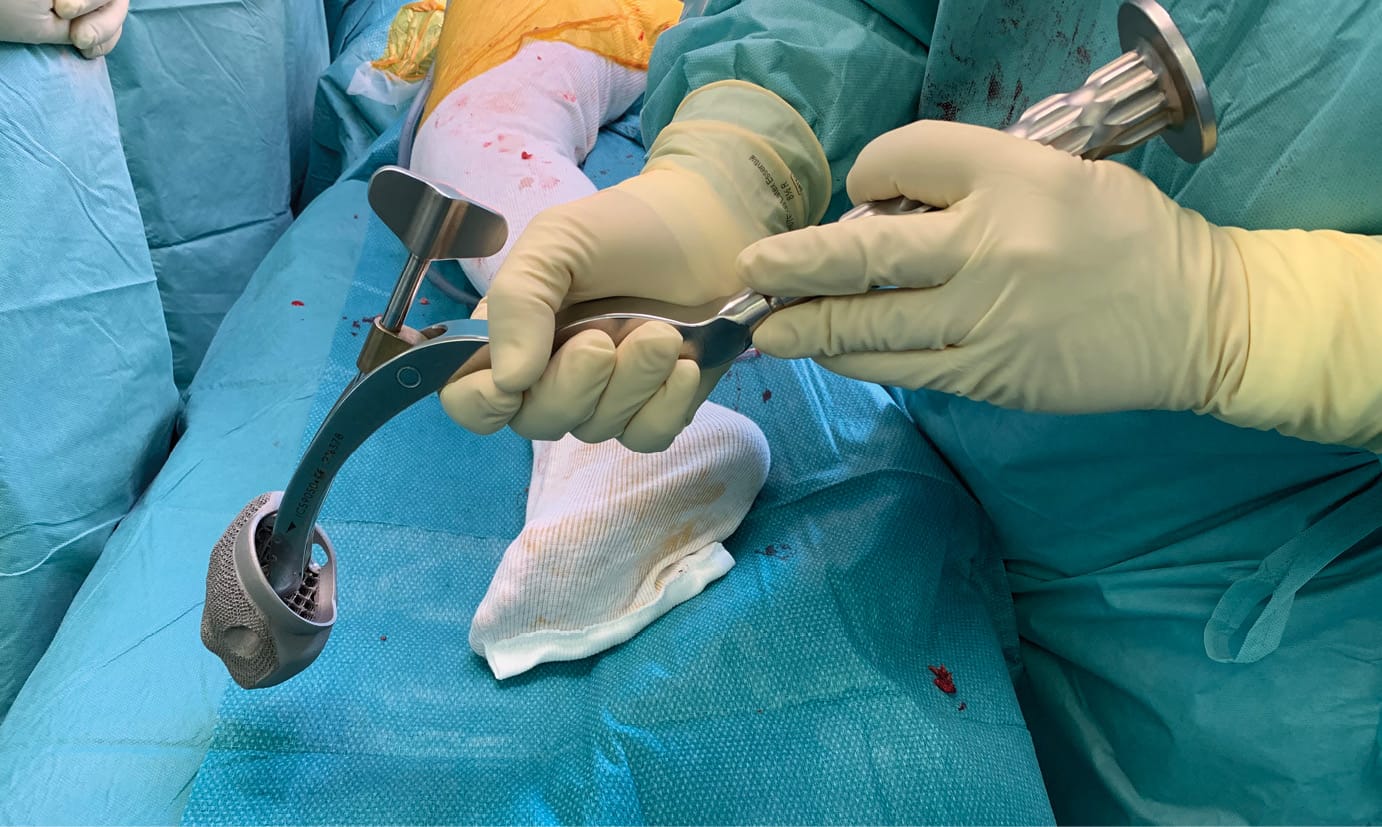

In one-stage procedures, bone debridement is identical to usual practice. Nevertheless, there is one fundamental adaptation: using a bur should be avoided as far as possible and instead a curette should be used to clean the acetabulum.

These technical principles are more sparing of bone and the aim is to limit further defects that could compromise press-fit fixation of the 3D implant.

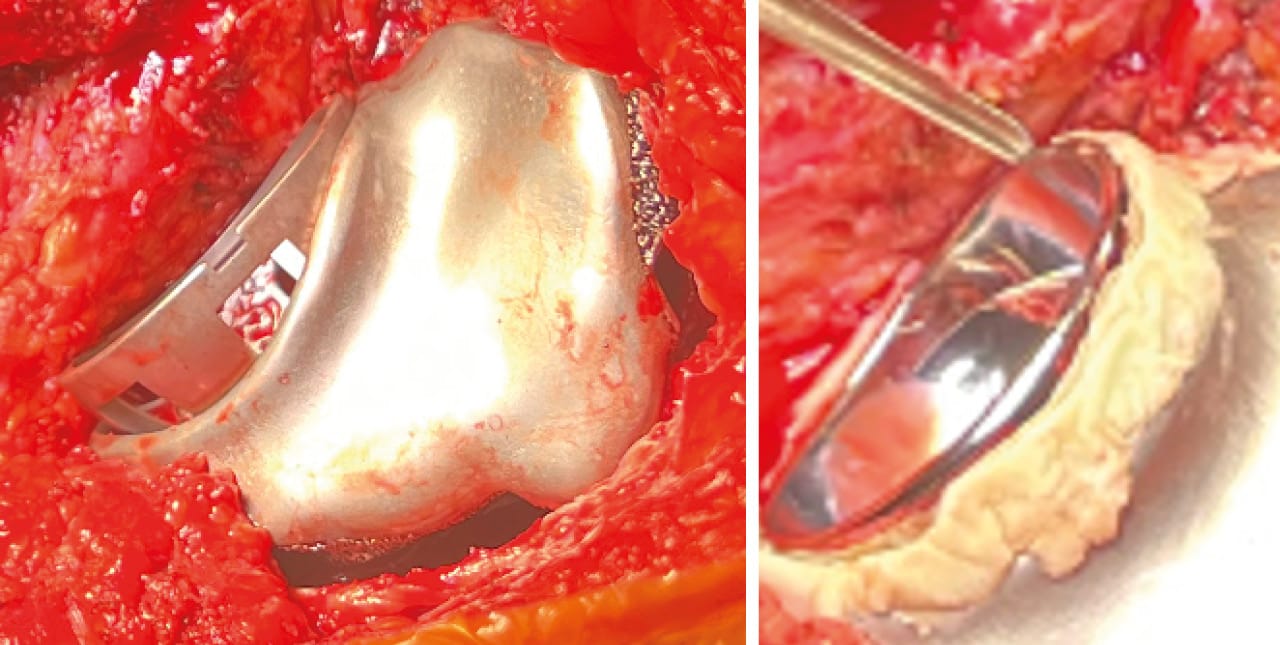

Implantation - Anchoring

A key issue when using custom 3D-printed implants, designed to be used without cement, is reproducing the planned press-fit anchoring. This was achieved in 81% of cases. In our experience, at least 50% depth of the native acetabulum and three anchorage points at the “equator”, or a minimum of two strong anchorage points positioned directly opposite each other, was needed and was often sufficient to achieve an uncemented primary fixation.

When we began using this technique, acetabular roof plates were routinely added in press-fit fixations, combined with screws in the ischiopubic and superior pubic rami.

We did not find any correlation between cementing or not cementing these implants and the type of bone loss being addressed.

Bone fragility was not a factor for failure or difficult primary fixation, even in one case of particularly advanced fragility that was managed as a second line option after a two-stage procedure was refused for this reason: uncemented fixation was delivered without perioperative or postoperative complications. However, in one case, uncemented implantation led to a fissure of the acetabular roof at the screw holes left by the explanted ring. “Preventive” bone repair using an acetabular roof plate before impacting the implant is recommended if there are screw holes in this area, especially if the patient presents concomitant bone fragility.

Using additional means of fixation

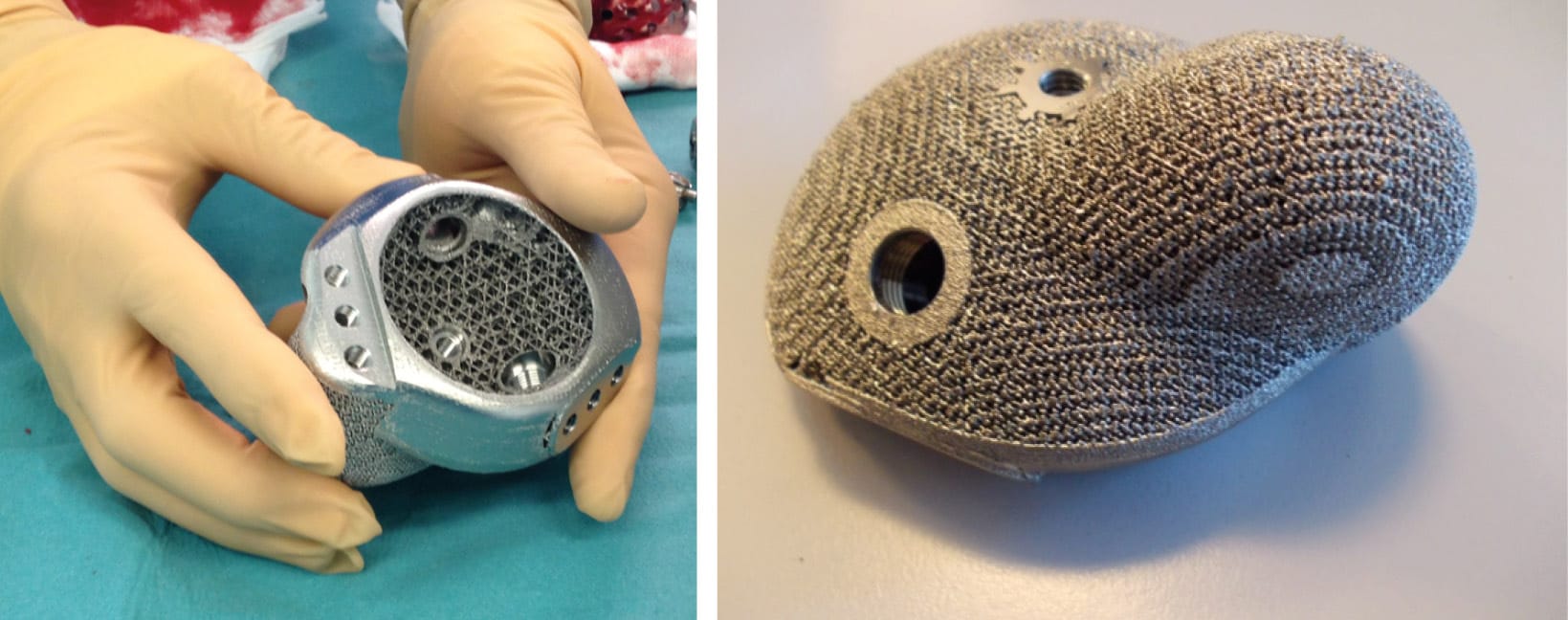

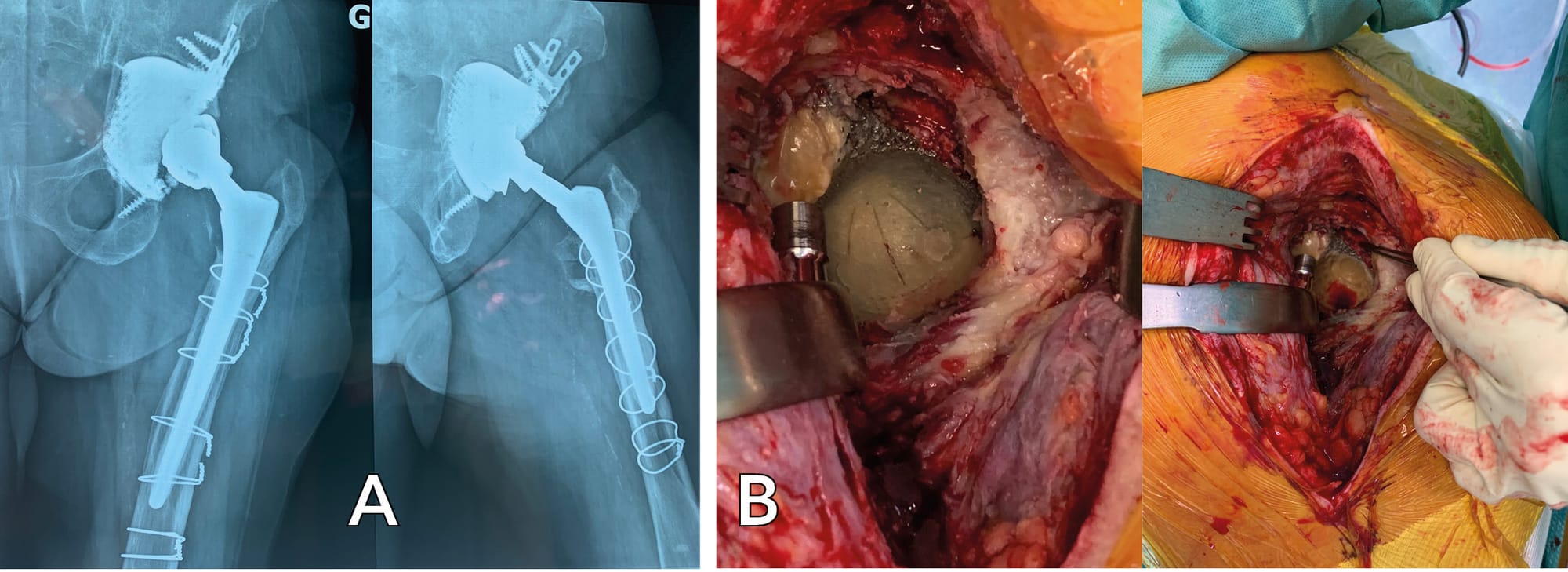

Initially, an acetabular roof plate or two plates was the method we used most. Now, they are no longer used. In every case that the planning allows it, we prefer to use screws in the acetabular roof, ischium and/or superior pubic ramus. More recently, we have chosen a single large calibre screw in the iliac isthmus. A potential alternative that could be considered is a central peg in the isthmus, but this was not used. This is because it is technically challenging to position the implant in the exact position planned and a 15-20° directional articulation plus oblong holes are integrated into the design for greater flexibility in aiming and fixation (Figures 3, 4 & 5). The only instrumentation required is an implant holder. There does not appear to be a need to use aiming devices or trial components.

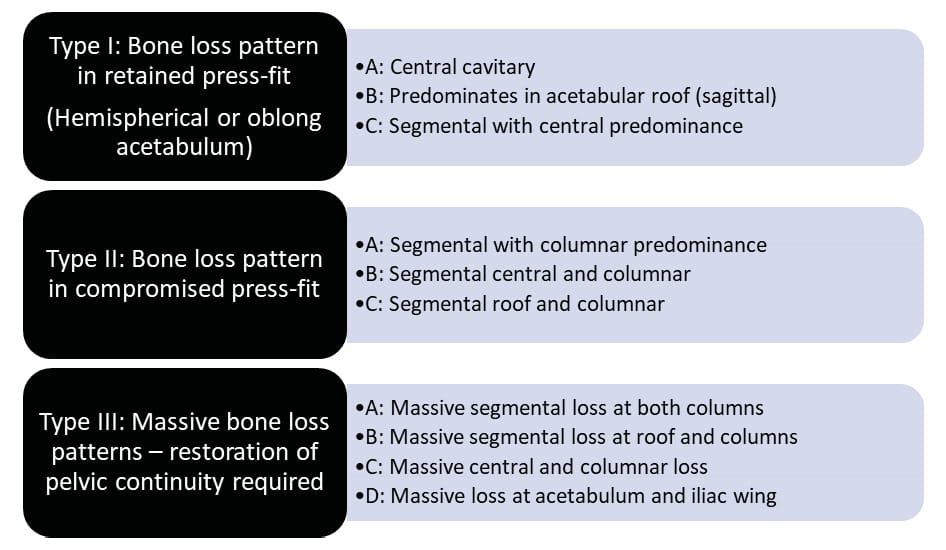

Proposed usage blueprint for a press-fit implant

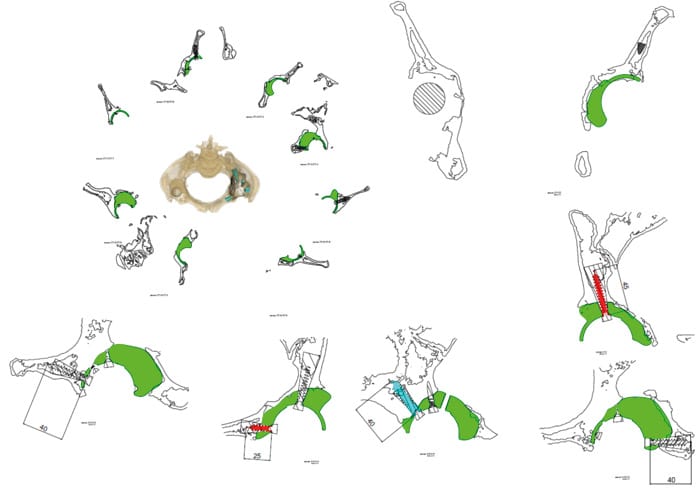

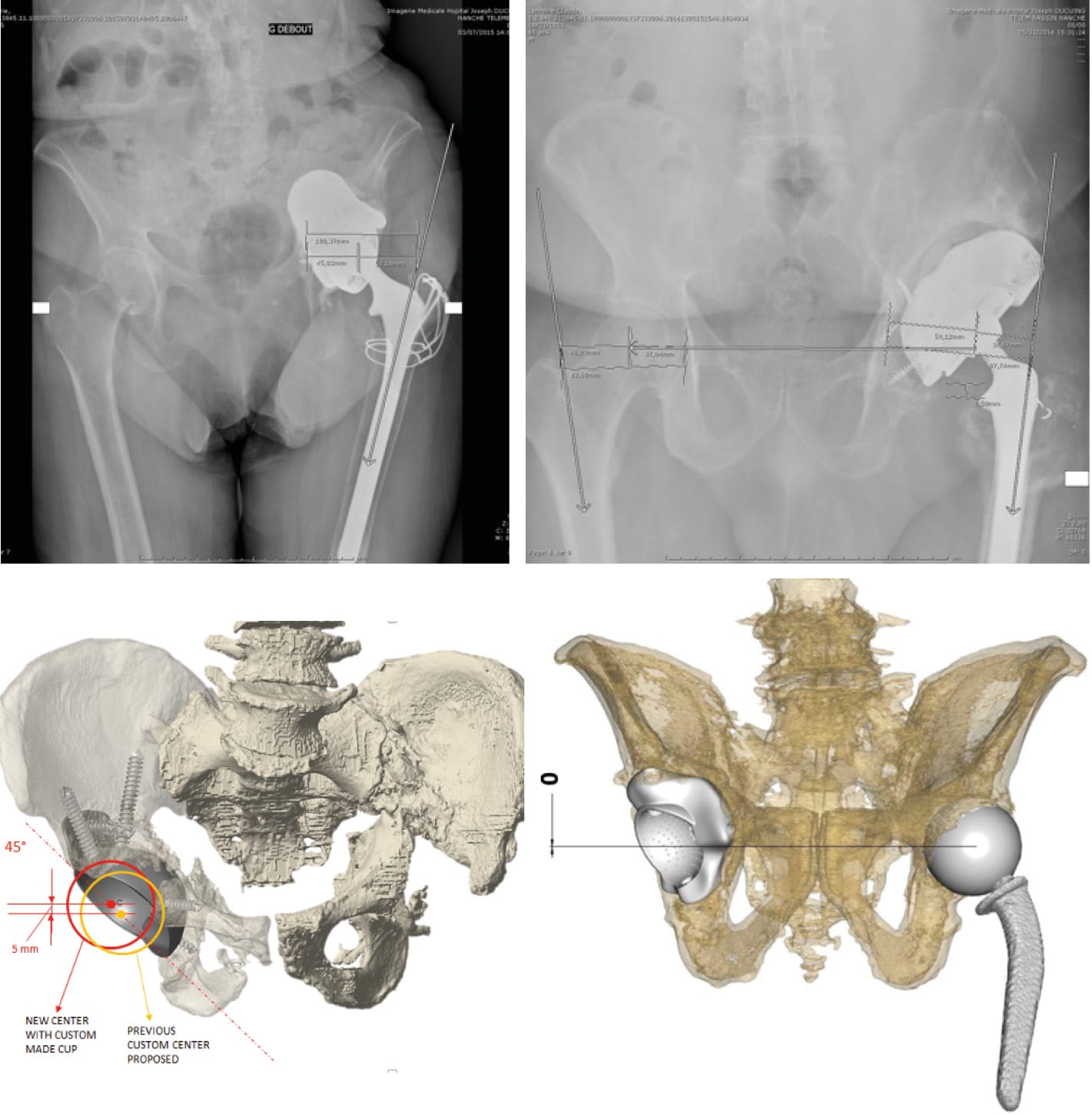

Although the various classifications published, as we have seen, can be cross-referenced to determine the geometry of defects and define custom implant designs, they are not always particularly informative when planning how to anchor the implant (Figure 6, 7 & 8). In this respect, perioperative adaptation is often needed.

We have therefore tried to define the factors that will help with the reasoning to make pre- and perioperative decisions by setting out a classification whose starting point is whether or not it is possible to achieve press-fit fixation.

This classification can be used preoperatively if, ideally, a CT 3D reconstruction is available.

In fact, through our practice we have identified a number of press-fit solutions:

- Equatorial press-fit

- Craniocaudal or sagittal press-fit (combined with anchorage at two or three points)

Starting from this observation, we can match up the graded bone loss and planning with the anticipated press-fit, falling into the following categories (Figure 9):

- "retained press-fit" for type I bone loss

- "potentially compromised press-fit", reassess during surgery, for type II bone loss

- and for type III, "press-fit subject to restoration of pelvic continuity or a priori unlikely".

Depending on this first point, the choice is then made on the basis of bone loss and the type of implant possible: first line or reconstruction or 3D custom-made, taking into account the very occasional decision for reconstruction by massive allograft.

The possibility of using custom-made implants can be considered for types IB extended, IC, IIB and IIC as an alternative to modular implants, depending on the extent of bone loss and for types IIIB and IIIC as an alternative to massive allograft (Figure 10).For all type III patterns, the indication is for reconstruction by a large custom-made implant or hemipelvic allograft. In these cases, paradoxically, a 3D-printed implant that is impacted and screwed can deliver sufficient primary stability to make a cementless one-stage procedure (where there is infection) possible. Out of the patients in our series who presented type III bone loss, only two required cemented fixation (Figure 11).

What impact does pelvic discontinuity have on the initial fixation and results?

The issue of pelvic discontinuity is reported in the literature as being a specific additional challenge 19,20. In these circumstances, using a custom triflange [21], DeBoer DK, Christie MJ, Brinson MF, Morrison JC. Revision total hip arthroplasty for pelvic discontinuity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):835-840. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00313[22] Taunton MJ, Fehring TK, Edwards P, Bernasek T, Holt GE, Christie MJ. Pelvic discontinuity treated with custom triflange component: a reliable option. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):428-434. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2126-1 or 3D-printed custom made implant [23] Friedrich MJ, Schmolders J, Michel RD, et al. Management of severe periacetabular bone loss combined with pelvic discontinuity in revision hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2455-2461. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2443-6 has been reported to have satisfactory short to medium term results. TM appears to demonstrate promising survival rates of 72 % after 6 years in these cases [5] Migaud H, Common H, Girard J, Huten D, Putman S. Acetabular reconstruction using porous metallic material in complex revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(1S):S53-S61. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2018.04.030.

In our experience, these discontinuities do not affect the quality of the initial cementless fixation. However, in two cases separate plates (at the acetabular roof and posterior column) were used prior to implant impaction to create a hold in the acetabulum and an opposing force to the press-fit to make sure it was successful. This workaround probably contributed to the success of this fixation and ensured that it lasted. An alternative possible technique in pelvic discontinuity is to anticipate an additional press-fit effect in the planning stage; there is no parameter in the preoperative decision making that can be put forward to define whether or not this technique should be used. When there is pelvic discontinuity, preoperative planning can never stand alone as adaptations during surgery will always be needed.

Except for in one patient, a good initial press-fit anchoring was not compromised over time. Anchoring failures in our series occurred early, within two months, and tended to be related to the learning curve in terms of matching patients to the right surgical technique. Cemented implants did not show any changes on radiography after even the longest follow-up.

In 90% of cases, these implants do not raise any issues in terms of primary anchoring, and their hold in the medium term. In summary, press-fit implantation requires some experience of the local conditions required and the technical adaptations during surgery, but it seems to be reasonable and appropriate.

Reconstruction using these porous metals, which adds a mean of 26 min (15–45 min) acetabular surgical time, simplifies an operation that is reputed to be complex. In the vast majority of cases, this amounts to a much shorter time than the graft–cage–cemented DM cup technique.

All patients were able to get up within 48 hours of surgery, and in 90% of cases immediate full weight bearing was resumed.

Combining a custom-made 3D-printed implant with a Dual Mobility (DM) component

The use of 3D-printed custom implants is inseparable from implantation of dual mobility components: there are a number of principles to follow with this “duo” concerning:

- The type of dual mobility cup used

- The implications for the design of the 3D-printed implant

- The implantation principles, bearing in mind the relative positioning of the two implants and the limitations imposed by DM cup size

There are three types of design that can be used, all of which are cemented: hemispheric DM cups, anatomic DM cups and components with an extended lip.

A hemispherical DM cup is a design that can be applied here to all kinds of cases. The “anatomic” design reduces the risk of anterior impingement and therefore of pain and instability or dislocation. This choice of DM cup should also be recommended when the lever arm is insufficient (short femoral neck, small size) and there is greater risk of cam impingement.

DM components with a lip offering optimum jump distance must be chosen in cases when there is a greater risk of dislocation and/or if reconstruction means that the 3D-printed implant needs to be positioned relatively vertically, since the lip can compensate for this positioning.

The DM cup size also needs to be taken into account: we find that cups under 48mm should be avoided, or recommend any size that means a 22mm diameter head can be avoided. This is an important factor because it does not restrict the potential solutions to issues of instability and dislocation in any subsequent revision.

From our perspective, the design of the 3D-printed implant must respect both the dip of the anterior wall and the elevation of the posterior wall. This design is able to reduce anterior and posterior impingement, especially if the orientation of the native acetabulum or the reconstruction imperatives mean fitting the 3D-printed component in a relatively neutral position. The combination with anatomic DM cups is our preferred option. During surgery the relative position of both components must be adjusted in real time (Figure 12).

Complications: management and prevention

Instability or dislocation

In the literature [5] Migaud H, Common H, Girard J, Huten D, Putman S. Acetabular reconstruction using porous metallic material in complex revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(1S):S53-S61. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2018.04.030, these are the most common complications, and this was also the case in our series: Out of our first 30 patients, six presented dislocations repeatedly during the first few weeks (20%) (Figure 13). In all of these cases, there were multiple causes: learning curve, managing design and positioning of the implant, or of the DM cup in relation to the implant, number of revisions, extent of muscle loss. We found a number of different solutions, including:

- Femur reconstruction, which always used a modular system, either a primary femoral component with a modular neck or a Wagner revision stem plus a modular head (Merete BioballTM). Large femoral components were implanted with an increase to the native offset.

- Optimising the design of the anterior wall of the 3D-printed implant, with the goal of avoiding anterior or posterior cam impingement.

- Improved management of the restoration of the centre of rotation in the planning stages (Figure 14)

- A DM cup with a minimum diameter of 48mm in the cage.

A single case of dislocation was noted subsequently in our series.

Two patients underwent partial revision: the DM component and two mobile parts were changed without revising the custom-made implant. During this process, we noted that these uncemented implants were perfectly intact and stable two months after they were fitted.

Neurological complications

We had no issues regarding secondary impacts on the sciatic nerve when using these implants, in contrast to the findings reported in the literature. This can probably be explained by a less significant “volume effect” than is seen with the Triflange implants and the footprint inherent with their fixation flanges.

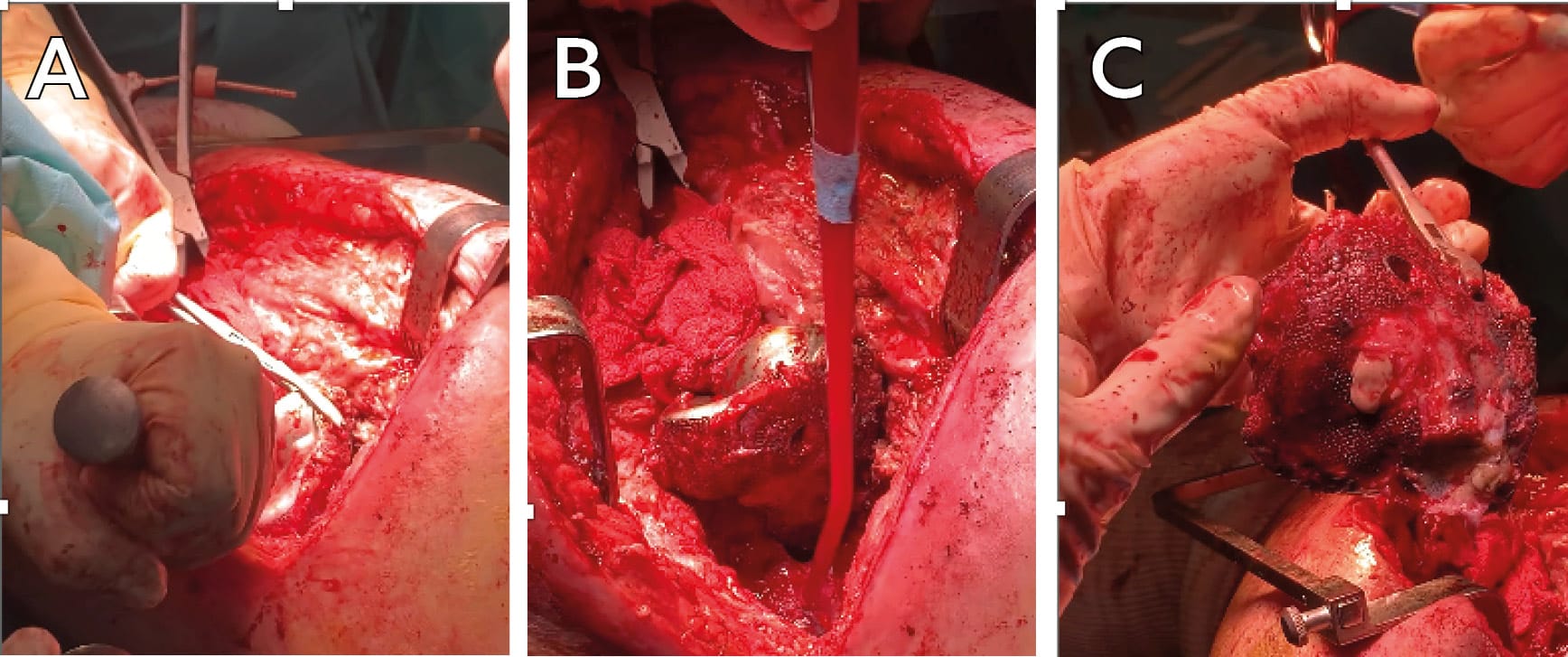

Mechanical complications

Three implants had to be revised due to early fixation failure: one case was treated for a periprosthetic infection with pelvic discontinuity and a total femur was fitted. This female patient presented a urinary complication that resulted in her early transfer. The management of functional factors was less than optimal here in view of the learning curve, and early disassembly was the outcome within a fortnight, in spite of the very good perioperative anchoring. The second case occurred following a fall two months after surgery and cannot be considered to be a fixation failure (Figure 15). The third failure was after 4 months in a physiotherapy session during weighted training; it was revised using another 3D-printed CMAI with press-fit implantation, and after 6 years there had been no complications.

We have validated three potential strategies to manage these mechanical complications:

- Revision with the same type of implant, either cemented or uncemented.

- Revision with a Triflange implant, with greater extra-acetabular support both at the iliac wing and the ischiopubic ramus and superior pubic ramus.

- Revision with a modular Trabecular TitaniumTM implant with wedges.

The last two cases involve cemented implantation with potentially more extensive approaches and greater risks to the sciatic nerve, especially for Triflange implants. In view of the manufacturing and delivery time frames for these different implants, it is possible to carry out a temporary head/neck resection with the femoral implant left in place, which is of course made possible through disconnecting the modular necks.

For septic revisions other than in our series, only Burastero2 reports on the medium-term results of custom-made 3D-printed implants. These two series both confirm that it is possible to use these implants for major defects in periprosthetic infection. The results are in agreement and are promising in terms of the quality of the planning, surgical feasibility, safety of use as a press-fit and the success rate on infection. Further information can be drawn from our series of our first 30 patients: 50% of procedures in periprosthetic infection were carried out in one stage, and these were compared to two-stage procedures. There was no significant difference between the two procedures in terms of successful management of infection. Additionally, the one-stage procedures showed no failures in the planning or implantation and this contradicts the findings from other publications, which recommend two-stage procedures with these implants [24] Di Laura A, Henckel J, Wescott R, Hothi H, Hart AJ. The effect of metal artefact on the design of custom 3D printed acetabular implants. 3D Print Med. 2020;6:23. doi:10.1186/s41205-020-00074-5.

Uncommon complications

New procedures involve new situations, and consequently questions about how to manage them.

Loosening of a cemented DM component after a fall with 3D-printed implant remaining in place

Eight years after acetabular revision, a fall led to loosening of a dual mobility implant without compromising fixation of a 3D-printed implant.

In this unusual situation, the 3D-printed implant remained in place and the remnants of DM cement were removed manually and by additional reaming. The hemispherical interface was drilled to make perforations and a further cemented dual mobility component was fitted (Figure 16).

There was excellent immediate recovery in this case and the functional outcome remained highly satisfactory after 3 years.

What about explantation of custom 3D-printed implants?

The issue of explantation of these implants and the potential to be able to consider other options for future reconstruction is a limitation of the use of 3D-printed implants.

We performed two explantations due to failed treatment of an infection and a new infection. Both of these implants had complex, non-hemispherical geometry. These extractions were performed using a Cauchoix osteotome with no significant bone loss. The anchoring was very good. A histopathological analysis was performed which found mainly fibrous tissue at the contact interface with the removed implant. (Figure 17)

Functional results

The patients in our series had extensive comorbidities. All patients were able to get up within 48 hours of surgery, and in 90% of cases immediate full weight bearing was resumed. 50% returned home.

In our experience, all patients experienced lasting improvement irrespective of the score used. This improvement was noted in the first month and a half for pain. For function, the outcome stabilised after 6 months on average. No functional result deteriorated after even the longest follow-up. The complexity of bone loss was not a factor for a poorer functional outcome. This finding correlated well with the stability of radiography over the same period. Satisfaction was consistently high, even if function was only partially improved. It should be emphasised that there was a high proportion of repeated revisions in our series: all patients except one had already had at least one hip replacement revision. Many comorbidities and numerous revisions account for this satisfaction in spite of relative functional outcomes and a significant number of postoperative complications.

There were no notable differences between the two groups of septic revision/aseptic revisions in terms of recovery of function and pain.

For septic revisions, 90% of patients did not have recurrence of infection with a minimum of 2 years of follow-up. This success rate is significant in patients who are often treated in the context of previous failures, multiple operations with poor local conditions and major comorbidities. This success rate is not inferior to that for periprosthetic infections treated by other techniques. We report no infectious complication specific to the use of this type of implant in 10 years, leading us to validate their use in periprosthetic infections. Infectious failures are secondary to two-stage procedures when the “one-stage” procedure has been excluded, and these are necessarily the more uncertain cases, and always complex.

There were no significant variations between the two groups of septic/aseptic revisions in terms of the kinetics and quality of functional recovery. The quality of the primary fixation of these implants probably goes some way to explaining this observation as well as an added value in immediate postoperative function. In our experience, all patients except one were able to immediately resume total weight-bearing post-surgery. This is undeniably an advantage for the rehabilitation of patients who present significant cumulative risk factors. Furthermore, it means that mean length of stay can potentially be reduced with the return home happening faster and more often. The medico-economic impacts need to be assessed so that the direct costs, which are greater than those of the standard techniques, can be compared with the indirect cost in dependent patients who have no options at present or who have undergone repeated failures. These issues also concern the different new implants. Tack et al. [25] Tack P, Victor J, Gemmel P, Annemans L. Do custom 3D-printed revision acetabular implants provide enough value to justify the additional costs? The health-economic comparison of a new porous 3D-printed hip implant for revision arthroplasty of Paprosky type 3B acetabular defects and its closest alternative. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(1):102600. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2020.03.012 and Wyatt et al. [26] Wyatt MC. Custom 3D-printed acetabular implants in hip surgery--innovative breakthrough or expensive bespoke upgrade? Hip Int. 2015;25(4):375-379. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000294 studied these costs; the former demonstrated that these 3D-printed implants custom-made using additive manufacturing offered added value over custom Triflange implants.

Conclusion

The correct use of 3D-printed implants custom-made by additive manufacturing in acetabular reconstruction requires an understanding of their potential place, the therapeutic alternatives and indications, especially in terms of bone loss.

It is also important to grasp the specific features of their design and combined use with a cemented dual mobility implant, and to understand the imperatives implied by the planning.

The technical aspects of the implantation procedure must follow both the rules for explantation and debridement and the principles of fixation in line with the geometry and volume of bone loss and of the implant.

The risks of complications must not be overlooked, particularly the risks of instability or dislocation and mechanical complications. Some technical adaptations involving a modular solution or implant and choosing a suitable cemented dual mobility implant type to use with it will minimise the risk of dislocation. After a learning curve, a more informed choice of “cementless” option resulted in fewer mechanical failures. We created a decision tree for the anchoring type according to bone loss pattern, and we have found this to be a useful tool for planning the strategy and/or managing it perioperatively.

After using these implants for over 10 years, our experience shows that they have demonstrated their worth in managing the most complex acetabular revisions in patients who frequently present histories of multiple implant operations and major comorbidities. The clinical results and patient satisfaction speak for themselves. These results bear witness to no significant difference between septic and aseptic revisions, with even the majority of septic revisions being performed in a single intervention.

References

1. Aprato A, Giachino M, Bedino P, Mellano D, Piana R, Massè A. Management of Paprosky type three B acetabular defects by custom-made components: early results. Int Orthop. 2019;43(1):117-122. doi:10.1007/s00264-018-4203-5

2. Burastero G, Cavagnaro L, Chiarlone F, et al. Clinical study of outcomes after revision surgery using porous titanium custom-made implants for severe acetabular septic bone defects. Int Orthop. 2020;44(10):1957-1964. doi:10.1007/s00264-020-04623-9

3. Gruber MS, Jesenko M, Burghuber J, Hochreiter J, Ritschl P, Ortmaier R. Functional and radiological outcomes after treatment with custom-made acetabular components in patients with Paprosky type 3 acetabular defects: short-term results. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):835. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-03851-9

4. Perticarini L, Rossi SMP, Benazzo F. Trabecular titanium tailored implants in complex acetabular revision surgeries: our experience at minimum 3 years follow-up. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020;34(5 Suppl. 1):45-49. IORS Special Issue on Orthopedics.

5. Migaud H, Common H, Girard J, Huten D, Putman S. Acetabular reconstruction using porous metallic material in complex revision total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2019;105(1S):S53-S61. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2018.04.030

6. Tokarski AT, Novack TA, Parvizi J. Is tantalum protective against infection in revision total hip arthroplasty? Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(1):45-49. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B1.34236

7. Laaksonen I, Lorimer M, Gromov K, et al. Does the Risk of Rerevision Vary Between Porous Tantalum Cups and Other Cementless Designs After Revision Hip Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(12):3015-3022. doi:10.1007/s11999-017-5417-3

8. Moličnik A, Hanc M, Rečnik G, Krajnc Z, Rupreht M, Fokter SK. Porous tantalum shells and augments for acetabular cup revisions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(6):911-917. doi:10.1007/s00590-013-1354-3

9. Konan S, Duncan CP, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Porous tantalum uncemented acetabular components in revision total hip arthroplasty: a minimum ten-year clinical, radiological and quality of life outcome study. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(6):767-771. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.98B6.37183

10. Paprosky WG, Perona PG, Lawrence JM. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty. A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9(1):33-44. doi:10.1016/0883-5403(94)90135-x

11. Ahmad AQ, Schwarzkopf R. Clinical evaluation and surgical options in acetabular reconstruction: A literature review. J Orthop. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S238-S243. doi:10.1016/j.jor.2015.10.011

12. Saleh KJ, Jaroszynski G, Woodgate I, Saleh L, Gross AE. Revision total hip arthroplasty with the use of structural acetabular allograft and reconstruction ring: a case series with a 10-year average follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):951-958. doi:10.1054/arth.2000.9055

13. Gozzard C, Blom A, Taylor A, Smith E, Learmonth I. A comparison of the reliability and validity of bone stock loss classification systems used for revision hip surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):638-642. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00107-4

14. Aprato A, Olivero M, Di Benedetto P, Massè A. Decision/therapeutic algorithm for acetabular revisions. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(14-S):e2020025. doi:10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10999

15. Johanson NA, Driftmier KR, Cerynik DL, Stehman CC. Grading acetabular defects: the need for a universal and valid system. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(3):425-431. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2009.02.021

16. Macák D, Džupa V, Krbec M. [Custom-Made 3D Printed Titanium Acetabular Component: Advantages and Limits of Use]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2021;88(1):69-74.

17. Baauw M, van Hellemondt GG, van Hooff ML, Spruit M. The accuracy of positioning of a custom-made implant within a large acetabular defect at revision arthroplasty of the hip. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):780-785. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.97B6.35129

18. Zampelis V, Flivik G. Custom-made 3D-printed cup-cage implants for complex acetabular revisions: evaluation of pre-planned versus achieved positioning and 1-year migration data in 10 patients. Acta Orthop. 2021;92(1):23-28. doi:10.1080/17453674.2020.1819729

19. Abdel MP, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Pelvic Discontinuity Associated With Total Hip Arthroplasty: Evaluation and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(5):330-338. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00260

20. Petrie J, Sassoon A, Haidukewych GJ. Pelvic discontinuity: current solutions. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(11 Suppl A):109-113. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.32764

21. DeBoer DK, Christie MJ, Brinson MF, Morrison JC. Revision total hip arthroplasty for pelvic discontinuity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):835-840. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00313

22. Taunton MJ, Fehring TK, Edwards P, Bernasek T, Holt GE, Christie MJ. Pelvic discontinuity treated with custom triflange component: a reliable option. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):428-434. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-2126-1

23. Friedrich MJ, Schmolders J, Michel RD, et al. Management of severe periacetabular bone loss combined with pelvic discontinuity in revision hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2014;38(12):2455-2461. doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2443-6

24. Di Laura A, Henckel J, Wescott R, Hothi H, Hart AJ. The effect of metal artefact on the design of custom 3D printed acetabular implants. 3D Print Med. 2020;6:23. doi:10.1186/s41205-020-00074-5

25. Tack P, Victor J, Gemmel P, Annemans L. Do custom 3D-printed revision acetabular implants provide enough value to justify the additional costs? The health-economic comparison of a new porous 3D-printed hip implant for revision arthroplasty of Paprosky type 3B acetabular defects and its closest alternative. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(1):102600. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2020.03.012

26. Wyatt MC. Custom 3D-printed acetabular implants in hip surgery--innovative breakthrough or expensive bespoke upgrade? Hip Int. 2015;25(4):375-379. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000294